ICAI follow-up review of 2022-23 reports

Letter from the Chief Commissioner

I had not expected to lead a fifth follow-up process, as we thought that this Third Commission would end last year, and our successor commissioners would take over. It turns out that the follow-up this year offers some cause for satisfaction. I am pleased that this year, we not only saw very good engagement from most of our interlocutors in government, but also an improvement in the responses to our recommendations, and some progress on difficult areas. It has been encouraging to increase the percentage of responses scored as adequate, with 57% compared to 43% last year.

As noted in the review, the government’s November 2023 White Paper on International Development has had a positive influence: “many of the priority themes and tools of the white paper are already becoming visible in the work to respond to ICAI recommendations”. Particularly striking has been the progress on FCDO’s transparency. In autumn 2022, when our review on transparency in UK aid was published, the commitment to transparency, which had diminished notably since the merger of the former Department for International Development (DFID) and the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), was in doubt. Following the appointment of Andrew Mitchell as minister of state for development and Africa later that month, we were pleased to receive a positive response from FCDO, on its commitment both to high standards and to greater openness on financial allocations. Progress since then has been impressive, even if there is further to go with other government departments and arm’s-length bodies.

We also saw a strong response to our review on UK aid to Afghanistan, with some good learning, including better use of scenario planning, even if this was partially offset by less good take-up of some of the recommendations from the more positive review of UK approaches to peacebuilding.

While on the downside there was very little progress in improving the value for money of aid provided to pay for refugees in the UK, it was encouraging to see the Treasury continuing to allow flexibility on the aid spending target, a move which itself diminishes value for money risks. Allowing an extra £2.5 billion over two years meant that in 2023, official development assistance was reported as 0.58% of gross national income. Although bilateral humanitarian spend was around £890 million compared to £4.3 billion on asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, far less would have been available for emergencies such as in Afghanistan, Yemen, Ukraine and Gaza if there had been a rigid approach. There was also more time to ensure prioritisation with better information from the Home Office.

Once again, we have seen that follow-up often needs to go on for more than one year. It was pleasing to see that the FCDO permanent under-secretary had instigated a formal process to ensure that all aid spending departments were accountable for the prime ministerial commitment to alignment with the Paris Agreement on climate change. In addition, three years on from ICAI’s review of the results of UK aid for nutrition, we could see much greater integration of nutrition outcomes into agriculture programmes.

Next year, a new Commission will lead the follow-up process. I am confident that ICAI will continue to use it to improve the effectiveness and value for money of UK aid.

Dr Tamsyn Barton, Chief Commissioner

Executive summary

This report presents the results of our follow-up exercise to assess progress made by aid-spending government departments and bodies on addressing recommendations by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). It covers 13 ICAI reviews in total: we follow up on nine reviews published in the last annual review cycle from July 2022 to July 2023, and we return again to four reviews published in previous cycles in order to address outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up exercise. Table 1 below gives an overview of the follow-up exercises conducted this year.

The follow-up review is one report, showing progress across a range of central themes and challenges in UK aid as well as drawing out cross-cutting issues and learning journeys from all of ICAI’s reviews produced in the 2022-23 review cycle. But the individual follow-ups of particular reviews presented in Section 4 of this report can also be read independently of the others. This year, two of the nine individual follow-ups were published earlier than the rest, in April 2024, and have subsequently been added into this follow-up review. The two are UK aid to India and UK aid to refugees in the UK.

Table 1: Reviews covered in this follow-up

| Review title | Publication date |

|---|---|

| Follow-ups | |

| Transparency in UK aid | 6 October 2022 |

| UK aid to Afghanistan | 24 November 2022 |

| The UK’s approaches to peacebuilding | 9 December 2022 |

| The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights | 18 January 2023 |

| UK aid to India | 14 March 2023 |

| UK aid to refugees in the UK | 29 March 2023 |

| The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework | 27 April 2023 |

| UK aid for trade | 6 June 2023 |

| UK aid to agriculture in a time of climate change | 28 June 2023 |

| Outstanding issues | |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme | 14 October 2020 |

| UK aid’s alignment with the Paris Agreement | 14 October 2021 |

| Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations | 22 March 2022 |

| The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19 | 14 July 2022 |

Scoring the government’s progress

Each review we follow up for the first time is given an overall score. As well as scoring each review we follow-up for the first time, we also score each individual recommendation within these reviews. Likewise, we score individual recommendations from reviews with outstanding issues from previous years.

We score the response to ICAI’s recommendations as adequate or inadequate, illustrated by a tick or a cross. An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow (the response is insufficiently implemented) and we are not convinced by the reasons for the slowness.

We recommend returning to issues where the government response has been inadequate, either as outstanding issues in the next follow-up or through future reviews.

Overview of the response to ICAI’s recommendations

In general, the government engaged actively and openly with this year’s follow-up process, helping ICAI to assess its performance in implementing recommendations from ICAI reviews published during 2022-23, as well as outstanding issues from previous reports. Overall, the government response to these recommendations was mixed, with 57% judged as having been adequately addressed, but this is notably higher than the proportion reported in last year’s follow-up review (43%), even including the long tail of older recommendations. ICAI is pleased to see this upward trajectory.

The mixed response was both between reviews and within reviews this year. In the case of ICAI’s reviews on transparency, the FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) and agriculture, we found a very positive response, while for our review of UK aid to refugees in the UK, the response to all recommendations was found to be inadequate. For the rest of the reviews that we followed up (or returned to as outstanding issues) this year, there was a combination of strong and less strong responses to individual recommendations. Some of these reviews were deemed adequate on the whole, despite some weaknesses, while others received an overall inadequate score, despite positive actions in some areas.

The positive highlights of this year’s follow-up exercise, which illustrate that ICAI’s recommendations have been well used, include the following:

- Transparency in UK aid: The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has reasserted its ambition to be an international leader in the field of aid transparency. While there is still work to be done, ICAI found strong progress across all its recommendations and a firm commitment from FCDO to continue on this trajectory. Our analysis suggests that FCDO is on track to receive a ‘very good’ score in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index.

- The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF): FCDO has made positive progress in promoting the PrOF at all levels, including simplifying and clarifying the guidance, and enhanced training and support for programme staff. FCDO has just mandated PrOF training for heads of mission with programme budgets over £1 million, which is an important next step. While ICAI would like to see the compliance and audit functions of FCDO’s aid management platform more fully used, the actions responding to this review’s recommendations have been positive and are likely to result in stronger programme management within FCDO.

- UK aid for agriculture in a time of climate change: The UK’s co-hosting of a global food security summit in November 2023, in the run-up to COP28, was a strong sign of UK commitment in this area. FCDO has made efforts to strengthen the focus on climate change and nutrition in UK aid for agriculture. The nutrition policy marker that helps the department pursue its nutrition objectives across UK aid programming has been updated to include FCDO’s commitment to monitor nutrition outcomes in commercial agriculture where they are part of the objectives, although negative impacts will not be monitored, and British International Investment (BII) will not be monitoring its impacts.

Outstanding issues we recommend returning to again next year

For other reviews, we found that the government response to some or all of the recommendations was inadequate. This is the last year of the current ICAI Commission, which will come to an end in June 2024. Next year’s follow-up review will be led by a new set of commissioners, who will make the final decision on which reviews to revisit.

We recommend returning to the following reviews as outstanding issues next year:

- UK aid to refugees in the UK: Returning to this review, ICAI found that in-donor refugee costs, far from reducing, actually increased from £3.7 billion in 2022 to £4.3 billion in 2023, constituting 28% of all UK aid that year. The severe value for money risks of this spend, mainly by the Home Office but also by other government departments, have not been reduced. ICAI will not return to assess the response on the two recommendations that were rejected by the government. However, four other recommendations (recommendations 3-6) were also inadequately addressed, and we recommend returning to these next year.

- UK aid to India: There were a number of improvements in response to ICAI’s review. FCDO has produced an initial theory of change on how its India portfolio contributes to poverty reduction, but this needs further work. Some modest FCDO projects in support of civil society groups are well designed and impactful. There are some stronger links between UK-funded research and investments made by BII, and significant improvements in BII’s interventions to mobilise private finance. However, while BII’s new India country strategy in July 2023 has convincing links to poverty reduction and a greater focus on inclusiveness, it does not yet seem to be shaping investments. BII’s India Quotient investment in particular has raised significant concerns which clearly warrant follow-up by ICAI. Thus, while the response to three out of five recommendations was adequate, given that recent BII investments in India raise concerns about the governance of BII as well as about its responsiveness to the International Development Committee and ICAI, and that there is still work to do to integrate considerations of inclusion in the India portfolio, we recommend returning to recommendations 1 and 4 next year.

- The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights: FCDO made good progress in implementing some of its most important commitments, in particular the creation of a democratic governance centre of expertise to provide guidance and support throughout the department, including the overseas network, new procedures to manage small annual projects better, and improved coordination with the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. FCDO is funding new central programmes to support individuals or organisations at risk of repression, but has not provided evidence of the reasons why it is not willing to review its diplomatic or fiduciary risk appetite in relation to these groups. ICAI remains concerned that FCDO is not able to retain sufficient numbers of governance advisers at senior levels or in embassies. Last but not least, with the Open Societies and Human Rights Strategy still in draft form, the government has not yet published a statement on its approach to democracy and human rights. We therefore recommend returning to recommendations 1, 2 and 4 next year.

- The UK’s approaches to peacebuilding: There were improvements in cross-FCDO and cross-government joint work on peacebuilding, more attention to learning and use of expertise, strengthened strategic direction through the White Paper on International Development and a strategic cross-government approach to climate security currently under development. However, ICAI’s recommendations on taking longer-term approaches to peacebuilding programming, on focusing efforts on countries where relationships were strong, and on improving accountability to affected populations, did not receive adequate attention from FCDO. There has also not been a change in the approach to travel risk based on learning from other donors. We therefore recommend returning to recommendations 2, 3, 4 and 6 next year.

- The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF): While the overall response to this review was adequate, we recommend returning to recommendation 2 to assess if FCDO has ensured that all programme staff and those with oversight roles have full access to the Aid Management Platform (AMP) and that the compliance and audit functions of AMP are fully used. We also recommend returning to how FCDO packages very small programmes on AMP and is strengthening the reliability of data published to Development Tracker (DevTracker), its public aid information portal.

- UK aid to agriculture in a time of climate change: FCDO has led a strong response to ICAI’s recommendations, and we find the overall response to this review to be adequate. We recommend, however, returning to recommendation 5 next year, to assess how FCDO and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology work together to integrate learning on development effectiveness into the design of future official development assistance (ODA)-funded agricultural research programmes.

We also recommend returning again to the following outstanding issues from earlier years:

- The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19: FCDO has still not been able to provide evidence that allows ICAI to verify whether the department has reached its target of delivering 25% of humanitarian support through local organisations. We therefore recommend returning to recommendation 2 again next year.

- Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations: FCDO has not yet engaged with the European Commission’s independent anti-fraud office, OLAF, and does not plan to use regular talks with OLAF for assurance purposes. ICAI has not seen evidence to ensure sufficient oversight of risk management and counter-fraud practice. We therefore consider the response to recommendation 3 to be inadequate and recommend returning to it next year.

- UK aid’s alignment with the Paris Agreement: We recommend returning to recommendation 4 next year to assess the UK’s engagement with developing country partners on Paris alignment.

Summarising progress on recommendations per review

Table 2: Overview of progress and scoring for individual reviews

| Our assessment of progress on ICAI recommendations | Score |

|---|---|

| Transparency in UK aid | |

| There has been a marked positive change in FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency, supported at ministerial and senior management level and promoted by a strengthened transparency team. There is stronger staff appreciation of the importance of transparency for FCDO’s development work. Systems integration, while not fully completed, now allows automatic publication of some key aid programme data (although not yet business cases and annual reports), and transparency work has become easier and less time-consuming for staff. Guidance has been clarified and training has been stepped up. FCDO appears to be on track to achieve a rating of ‘very good’ in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index. While FCDO needs to continue the same trajectory to reach its ambition to regain its global leadership role in aid transparency, its improvements are significant. The department does, however, need to support its arm’s-length bodies and other government departments to raise their aid transparency ambitions. This would include support to make publication of aid data to International Aid Transparency Initiative standards easier through, for example, improving the accessibility of DevTracker for non-FCDO users. |  |

| UK aid to Afghanistan | |

| There is evidence of learning activities and progress across the three recommendations of ICAI’s report, particularly regarding FCDO’s improved use of scenario planning. The department is putting in place new guidance and mechanisms for learning about its work in fragile and conflict-affected settings, with the aim, among other things, of mitigating the risk of repeating the mistakes ICAI identified in Afghanistan. The mechanisms for internal challenge are visibly stronger, showing that the recommendations of the Chilcot Inquiry, conducted after the Iraq war, still have currency and relevance seven years after their publication. ICAI continues to take the view that the use of ODA to pay the salaries of police officers deployed on paramilitary tasks amounts to an inappropriate use of ODA to fund paramilitary operations. |  |

| The UK’s approaches to peacebuilding | |

| The response to ICAI’s recommendations on the UK government’s peacebuilding work has been variable. We found some notable improvements in cross-FCDO and cross-government work on peacebuilding, more attention to learning, and the use of expertise and the internal challenge function, as well as strengthened strategic direction through the November 2023 White Paper on International Development and a strategic cross-government approach to climate security, which is currently under development. However, the response to four out of six recommendations was inadequate. FCDO’s conflict-related programming continues to operate mainly on annual cycles, while peacebuilding work by its nature requires long-term, patient engagement and trust-building. There is a lack of strategic focus on countries where relationships are strong, there is still insufficient appreciation and understanding of the principle of accountability towards the communities within which FCDO-funded interventions take place, and there has not been a change in the approach to travel risk based on learning from other donors. |  |

| The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights | |

| FCDO’s responses to ICAI’s review have mainly been positive, with many relevant actions. The department has created a democratic governance centre of expertise, developed new procedures to manage small annual projects better, and improved coordination with the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. FCDO is funding new programmes to support individuals or organisations at risk of repression, but remains relatively risk-averse when it comes to willingness to consider trade-offs between diplomatic relations or fiduciary risks and protection of human rights defenders, journalists and other civil society actors. ICAI remains concerned that FCDO is not able to retain enough governance advisers at senior levels, including staff in embassies, as these positions are important to assure the impact and value for money of ODA for democracy and human rights, as well as to maintain FCDO’s international reputation of thought leadership in this area. With the Open Societies and Human Rights Strategy still in draft form, the government has not yet published a statement on its approach to democracy and human rights. |  |

| UK aid to India | |

| FCDO has taken steps to direct its aid portfolio towards poverty reduction through developing a theory of change. The department recognises the need for further work on its draft theory of change, and ICAI would like to see stronger evidence on how interventions funded by ODA will contribute to inclusive growth and address persistent ‘pockets of poverty’ in India. Some modest FCDO projects in support of civil society groups are well designed and impactful. There are some stronger links between UK-funded research and investments made by British International Investment (BII), the UK government’s development finance institution, and significant steps forward in BII’s interventions to mobilise private finance. BII published a new India country strategy in July 2023 with convincing links to poverty reduction and a greater focus on inclusion, including attention to regional inequalities within India. However, the new strategy does not yet seem to be shaping investments sufficiently, and additionality is still not a consistent focus. We found recent BII investments in Indian funds that pose significant reputational risks to BII and have questionable links to poverty reduction. These include investments in the cosmetics industry as well as social media platforms featuring hate speech, abuse of women and offers of sexual services. We found that such investments were made two months after BII’s CEO, in April 2023, had reassured Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) that, following concerns about an investment in a cosmetic surgery clinic, future investments in India would only be made if there was a ‘compelling argument’ relating to inclusion and sustainability, which was not the case in these subsequent investments. These recent BII investments in India raise material concerns about the governance of BII as well as about its responsiveness to the IDC and ICAI. |  |

| UK aid to refugees in the UK | |

| In-donor refugee costs have continued to increase, from £3.7 billion in 2022 to £4.3 billion in 2023. Hotel costs are the main drivers of the increase. Value for money concerns have not diminished and standards of support do not seem to have tangibly improved. The introduction of some flexibility into the 0.5% aid commitment, better communication from the Home Office to FCDO, and improved planning and risk management by FCDO have played some role in helping FCDO cope better with the stresses created by in-donor refugee costs, but have not dealt with their underlying factors. The fact that gross national income for 2023 was considerably higher than forecast is one of two significant factors in smoothing out the impact on FCDO, the other being an additional £2.5 billion of ODA resources over 2022 and 2023 provided by the Treasury in response to the unprecedented spend by the Home Office. The UK government has not revisited its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs and appears to be taking a maximalist approach to reporting these costs compared to most, if not all, large donors. While we saw some improvements in how the Home Office manages its large-value asylum accommodation and support contracts, value for money and safeguarding concerns continue, and the Home Office has not found a route out of short-term crisis management towards longer-term solutions for asylum accommodation. The Illegal Migration Act (IMA) is an important unknown piece in this puzzle: if it is fully implemented, in-donor refugee costs will drop dramatically. Meanwhile, the Home Office is reporting accommodation costs as ODA for the cohorts of asylum seekers who arrived by irregular routes (and therefore would fall under the IMA) after 8 March 2023, when the Illegal Migration Bill was introduced to Parliament, and after 20 July 2023, when it received royal assent and became an Act, but it is not progressing their asylum applications as it is assumed that they will be deported. This approach is untenable as a new backlog of cases in limbo is building up fast, at considerable human and financial cost. |  |

| The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework | |

| FCDO has made progress in promoting the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) at all levels, including an enhanced learning offering and continuously improving support for programme staff. FCDO has now mandated PrOF training for heads of mission with programme budgets over £1 million. ICAI strongly supports this as an important part of ensuring change at this level, which remains the key challenge. ICAI remains concerned, however, that the compliance and audit functions of the Aid Management Platform are not fully used. Work on increasing the reliability of data published to DevTracker needs to continue. FCDO has made a commitment to establish a comprehensive three-to-five-yearly consultation process to strengthen the PrOF’s clarity, relevance and accessibility, but has not yet planned this in detail. In the meantime, the department has made incremental but important improvements to the PrOF through a range of mechanisms. |  |

| UK aid for trade | |

| Although still in the early stages, FCDO has made some notable progress, and is moving back to closer alignment of its support to the multilateral organisations underpinning the rules-based system governing trade. The department has plans to strengthen the evidence base on how to deliver pro-poor and inclusive trade policy and programming and to improve coordination and complementarity under the Trade Centres of Expertise. FCDO has strengthened the focus on primary purpose in its programme guidance, reducing (albeit not eliminating) the risk that officials may select interventions with relatively lower potential for poverty reduction to secure benefits for the UK. Most of the reported progress focuses on FCDO’s Trade for Development team and its programmes, with limited evidence provided for this follow-up on aid for trade programmes managed from embassies and high commissions. However, ICAI notes that FCDO has taken concrete actions to strengthen transparency and predictability, which are key to its ongoing work to rebuild its reputation as a trusted development partner after the aid reductions, even if there is more to be done. |  |

| UK aid to agriculture in a time of climate change | |

| There has been something of a step change in the visibility of the UK’s commitment to, and leadership on, agriculture, as seen with its co-hosting of a global food security summit in November 2023, in the run-up to COP28. FCDO has mounted a strong response to ICAI’s recommendations to improve the UK’s aid to agriculture in a time of climate change. It has developed new guidance on use of international climate finance for agriculture programmes and has made progress in improving the focus on nutrition. A nutrition policy marker has been updated to include FCDO’s commitment to monitor nutrition outcomes in commercial agriculture programmes with nutrition objectives, although negative impacts will not be monitored, and BII will not be monitoring its impacts. Most of the improvements noted in this follow-up have been led by FCDO’s central teams covering food security, agriculture and land, and nutrition, its Research and Evidence Directorate, and its food and agriculture cadre, while weaknesses remain in cross-government coordination and the work of BII, UK Research and Innovation and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. |  |

Table 3: Overview of progress on outstanding issues from earlier reports

| Outstanding issue | Our assessment of progress since last year |

|---|---|

| UK aid’s alignment with the Paris Agreement | |

| Last year’s follow-up found that the government was not reporting publicly on its progress in achieving Paris alignment, and it was not clear how other government departments than FCDO were planning to align their aid with the Paris Agreement. There was a lack of government engagement with developing countries on Paris alignment. We therefore returned this year to recommendations 2, 3 and 4 for a second time. | This year’s follow-up review found significant improvements in cross-government reporting on Paris alignment. Responding to a formal request from FCDO’s permanent under-secretary, by February 2024 all ODA-spending departments had sent an account to FCDO outlining their internal approaches to aligning their ODA spending with the Paris Agreement, supported with evidence. It remains a concern, however, that these reports are not in the public domain. FCDO leads a cross-government Paris alignment working group, which has helped departments develop their capacity to establish their own Paris alignment processes and to use FCDO-created tools such as climate and environment risk assessments. A climate, environment and nature (CLEAN) helpdesk is about to be launched, designed to respond to climate and biodiversity assistance requests on Paris alignment and the government’s nature-proofing commitment. The CLEAN helpdesk, once operational, may also help UK embassies deepen their engagement with partner governments, but there is currently little evidence to suggest that the UK government is intensifying its engagement with developing countries on Paris alignment. Overall, there has been an adequate response to recommendations 2 and 3, apart from the lack of a public account of the government’s Paris alignment commitment. We recommend, however, returning next year to assess the UK’s engagement with developing country partners on Paris alignment. |

| The UK’s humanitarian response to COVID-19 | |

| Last year’s follow-up found that FCDO had yet to address ICAI’s recommendation to undertake a formal afteraction review of the COVID-19 response to inform its future pandemic responses. It also noted that robust evidence had not yet emerged to show that FCDO was expanding the localisation of its humanitarian support. We therefore decided to return to these two recommendations again this year. | In this year’s follow-up exercise, FCDO told ICAI that a conscious decision had been made not to do a ‘monolithic’ after-action review, since the advice from scientists was not to prepare to “fight the same war again”. Instead, the government has broken down learning to look at different aspects of the COVID-19 response, incorporating lessons into different policies, including an Epidemic and Pandemic Readiness Framework, to enable a more agile and better prepared response in the future. This differs from ICAI’s original recommendation of an after-action review, but given the time elapsed, we consider this an adequate response. There were also positive developments in the government’s commitment to localisation. The White Paper on International Development promotes an ambitious, systemic approach to ensure locally led development is pursued across aid sectors, but work on this demands strong and sustained political will. Meanwhile, ICAI is still not able to confirm whether FCDO has reached its target of delivering 25% of humanitarian support through local organisations. We therefore recommend returning to recommendation 2 again next year. |

| Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations | |

| Last year’s follow-up of this review concluded that while the response to this review was generally good, action was inadequate on updating fraud risk assessments of UK aid spent through the European Commission. The government noted that the difficult political context around UK-EU relations had posed challenges for addressing this recommendation, but ICAI judged that the government could have done more within these constraints to engage on fraud oversight. | Since last year, modest progress has been made in engaging with the European Commission on the issue of fraud. The government told ICAI that official-level discussions with the Commission involved the first discussions on the issue of fraud risk since 2018. However, FCDO has not made contact with the Commission’s independent anti-fraud office, OLAF. Overall, we consider the response to be inadequate and recommend returning to it next year. |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme | |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme was published in October 2020. One of the five recommendations was that the “UK government should publish a clear statement of its overall objectives and approach to using UK aid to tackle modern slavery internationally”. This is the third year that ICAI follows up on this recommendation, since such a statement has yet to be produced. | The government’s response continues to be inadequate, because there has still been no published statement of its international objectives and approach. ICAI will not, however, follow up this recommendation again, since we see limited traction for our efforts to clarify the UK government position on using aid to tackle modern slavery in the current political context. |

1. Introduction

1.1 The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) provides robust, independent scrutiny of the UK’s official development assistance (ODA), to assist the government in improving the effectiveness and impact of its interventions and to assure taxpayers that where there is poor value for money of UK aid spending, it will be brought to the attention of the public. Our main vehicle for this scrutiny is the publication of reviews on a broad range of topics of strategic importance in the UK’s aid programme. A vital part of these review processes is our annual follow-up, where we return to the recommendations from the previous year’s reviews to see how well they have been addressed.

1.2 This report provides a record for the public and for Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) of how well the UK government has responded to ICAI recommendations. The follow-up process is also an opportunity for additional interaction between ICAI and responsible staff in aid-spending departments, offering feedback and learning opportunities for both parties. The follow-up process is central to our work to support learning and improvements in UK aid delivery and to ensure maximum impact from reviews.

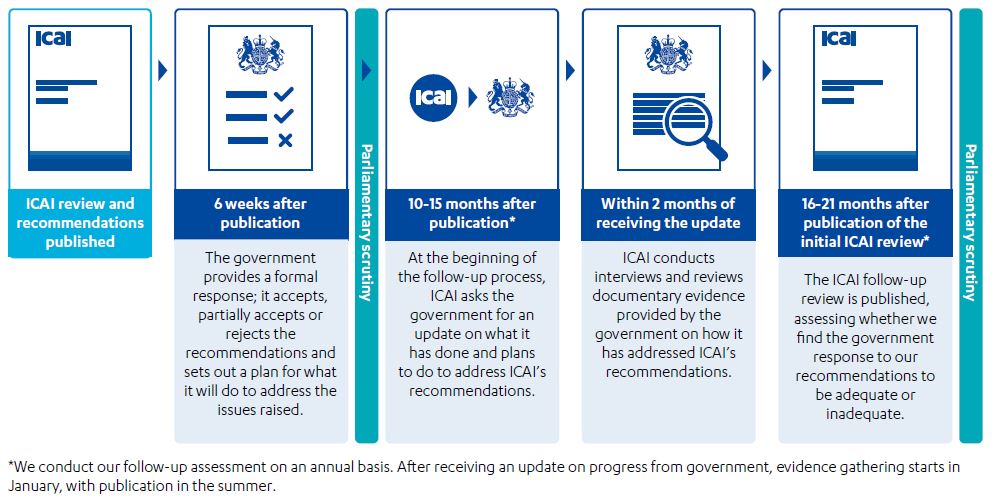

Figure 1: Timeline of ICAI’s annual follow-up process

1.3 The follow-up process is structured around the recommendations provided in each ICAI review (see Figure 1 above for an illustration of the process). Soon after the original ICAI review is published, the government provides a formal response (within six weeks). The response sets out whether the government accepts, partially accepts or rejects ICAI’s recommendations and provides a plan for addressing the issues raised. The IDC may then organise a specific hearing or call ICAI witnesses to its own inquiries. The formal follow-up process starts around a year after the publication of the original review (sometimes sooner and sometimes later depending on when in the annual review cycle the original review was published). The results of this follow-up are presented in the annual follow-up review.

1.4 To start the follow-up exercise, ICAI asks aid-spending departments and bodies for an update on what they have done and plan to do to address last year’s recommendations. This is followed by an evidence-gathering stage, where we investigate the extent to which the government has done what it promised and – considering any additional relevant actions – determine if this is an adequate response. The findings are reported and scored in the follow-up review. After publication, there is parliamentary scrutiny of the review’s findings.

Scoring the follow-up exercises

1.5 Each review we follow up for the first time is scored using a tick or a cross, depending on whether we find the overall progress adequate or inadequate. As well as scoring each review we follow-up for the first time as adequate or inadequate, we also score each individual recommendation within these reviews. Likewise, we score individual recommendations from reviews with outstanding issues from previous years. The score takes into consideration the wider context, including external constraints, in which government actions have taken place. It also considers the time the relevant government department or organisation has had to plan and implement changes.

1.6 An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow and we are not able to judge their effectiveness (the response is insufficiently implemented).

1.7 The third factor – the adequacy of implementation – is not a simple question of checking if plans have been put into practice yet. We take into consideration how ambitious and complicated the plans are, and how realistic their implementation timelines are. Some changes are ‘low-hanging fruit’ and can be achieved quickly, while others demand long-term dedicated attention and considerable resources. An inadequate score due to slow implementation will only be awarded if ICAI finds the reasons provided for lack of implementation insufficient.

1.8 This year’s follow-up review covers nine ICAI reviews from last year with a total of 42 recommendations, as well as outstanding issues from four past reviews with a total of 7 recommendations.* After briefly setting out our methodology, we present an account of progress on the nine reviews and four past reviews with outstanding issues covered by this year’s follow-up review. We sum up with a brief conclusion and a list of the reviews and recommendations that we recommend returning to again next year.

* Two of these recommendations, in the UK aid to refugees in the UK rapid review, were rejected by the government. While ICAI commented on the issues covered by these recommendations, it did not score the adequacy of the government’s actions

2. Methodology

2.1 When we follow up on the findings and recommendations of our past reviews, we focus on four aspects of the government response:

- Whether the actions proposed in the government response are likely to address the recommendations.

- Progress on implementing the actions set out in the government response, as well as other actions relevant to the recommendations.

- The quality of the work undertaken and how likely it is to be effective in addressing the concerns raised in the review.

- The reasons why any recommendations were only partially accepted or, in the case of two recommendations covered by this year’s follow-up, rejected.

2.2 We begin by asking the relevant government department or organisation to prepare a brief note, accompanied by documentary evidence, summarising the actions taken in response to our recommendations. We then check that account through interviews with responsible staff, both centrally and in embassies, and by examining relevant documentation, such as new strategic plans and annual reviews. Where necessary or useful, we interview external stakeholders, including other UK government departments, multilateral partners and implementers. To ensure we maintain sight of broader developments, we also assess whether ICAI’s findings and analysis have been influential beyond the specific issues raised in the recommendations, as well as whether changes in the environment have affected the relevance or urgency of particular recommendations.

2.3 The follow-up process for each review concludes with a formal meeting between a commissioner and the senior civil service counterpart in the responsible department. At the end of the follow-up process, we identify issues that warrant a further follow-up the next year. The decision takes into account the continuing strategic importance of the issue, the action taken to address it, and whether or not there will be other opportunities for ICAI to pursue the issue through its future review programme.

2.4 We also use the follow-up process to inform internal learning for ICAI about the impact of our reviews on UK aid and how we communicate our findings and recommendations to achieve maximum traction with the government.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

The follow-up review addresses the adequacy of the government response to ICAI’s recommendations. Its findings are based on checking and examining the government’s formal response, and its subsequent actions in relation to the recommendations from the review. The time and resources available for this evidence-gathering exercise are limited, and not comparable to a full ICAI review.

3. Cross-cutting issues and learning journeys

Introduction

3.1 The UK government launched its White Paper on International Development on 20 November 2023. The Minister for Africa and Development, Andrew Mitchell, used the opportunity of the Global Summit on Food Security, co-hosted in London by the UK on the same day as the launch, to present the white paper as the UK’s “longer-term vision for addressing critical global challenges” to a wider international audience. After some years of turbulence in official development assistance, with the creation of the newly formed Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office followed by several rounds of aid budget reductions, and the rise of in-donor refugee costs to consume almost a third of all UK aid (28% in 2023), the white paper is part of the effort to return to a strategic, longer-term approach to UK development assistance.

3.2 The white paper’s core focus areas are the challenges of climate change and the environment; inclusion, equity and social protection; and conflict, fragility, disasters and food security. It sets out four main ways in which the UK will work to tackle these challenges: mobilising investment; fostering partnerships, including with the private sector; supporting locally led action; and promoting collaboration on research, innovation and new technologies. The white paper also re-establishes the UK’s commitment to be an international leader in aid transparency.

3.3 ICAI’s follow-up review this year suggests that many of the priority themes and tools of the white paper are already becoming visible in the work to respond to ICAI recommendations. We found that the white paper has helped teams to underpin, promote and gather momentum around actions and priorities in areas such as aid transparency, nutrition, locally led development, aid for trade, and conflict and climate. As such, its publication seems to have had the effect of galvanising support and providing levers for action in these priority areas. In this section we provide two brief accounts of ‘learning journeys’, where the white paper has also played a role. These are short case studies showcasing reflection, planning and action that have supported notable change in particular portfolios, seen through the lens of the annual ICAI review and follow-up cycle.

Learning journeys

Box 2: Learning journey – aid transparency

Concerns about a reduction in aid transparency have been voiced in a range of ICAI reviews conducted after the merger of the former Department for International Development (DFID) and the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in 2020. As such, transparency has also been a frequent topic of ICAI’s annual follow-up reviews. The 2020-21 follow-up review included “problems of monitoring, record-keeping and transparency” as a cross-cutting issue. The review noted that “there had been a reduction in the comprehensiveness of record-keeping and documentation of the UK aid programme since the merger”, which affected FCDO’s ability to assess value for money, learn and build on previous experience. The follow-up review also noted concerns about the transparency of the aid programmes of other government departments, first raised in its review How UK aid learns, and that “FCDO continued to be absorbed by the process of developing its own systems, policies and strategies, which limited its ability to support efforts to develop a more coherent and joined-up approach to monitoring and evaluation, learning and transparency across the UK aid programme”.

The Aid Transparency Index of 2022 was a visible sign of the decline in UK aid transparency. ICAI noted in last year’s follow-up review that the index “highlighted notable declines in external transparency of aid

across the main departments managing the UK aid programme”. FCDO received a score of ‘good’ on the 2022 index, down from DFID’s consistent score of ‘very good’ since the index was first launched by Publish What You Fund in 2012.

In October 2022, ICAI published its rapid review of Transparency in UK aid. The review was not scored but concluded that while DFID had been an international leader in promoting aid transparency, FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency had come into question. In January 2023, ICAI’s review of The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights found that the UK was “at risk of being declared an ‘inactive’ member by the Open Government Partnership, a coalition of 77 countries which assists governments in becoming more transparent, accountable and responsive”, a situation which suggested that the problem was wider than in the context of aid.

The Transparency review’s four recommendations were all aimed at supporting a return to a strong UK commitment to aid transparency, arguing that this goes hand in hand with excellence in development cooperation. This year’s follow-up exercise found that since the Transparency review was published, there has been a marked positive change in FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency, supported at ministerial and senior management level and promoted by a strengthened transparency team. The November 2023 White Paper on International Development is a very visible sign of this change. It reconfirmed the ambition that “the UK will take a lead in promoting aid transparency internationally” and committed FCDO to display the “highest transparency standards among all foreign ministries globally”. In line with ICAI’s recommendation, the white paper also committed FCDO to attain a ‘very good’ score in the next Aid Transparency Index, to be published in July 2024.

Details of the rise in staff appreciation of the importance of transparency for FCDO’s development work, as well as the strengthening of systems for the publication of key aid programme data, can be read in the section of this follow-up review assessing progress against the four transparency recommendations (see paragraphs 4.2 to 4.23).

Achieving the ambition to regain a global leadership role in aid transparency will require sustained commitment over time. The emphasis placed on transparency in the white paper may also spur other government departments and FCDO’s own arm’s-length bodies towards greater transparency. The white paper commits to conduct a “UK ATR [aid transparency review] assessing the transparency performance of UK government departments with significant ODA budgets”. This would be a useful step in the UK government’s journey back towards greater aid transparency.

Box 3: Learning journey – nutrition

ICAI first reviewed UK aid in support of nutrition results in 2014, followed by a second nutrition review in 2020. This latter review, Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition, was awarded a green-amber score, acknowledging that the former Department for International Development (DFID) had surpassed its targets for providing nutrition services in some of the world’s poorest countries. The review noted that “given that DFID only started scaling up its work on nutrition in 2013, the positive contributions of UK aid in this area are impressive”. The decision to scale up was seen as appropriate, considering the continuing high levels of stunting and wasting in children and the fact that “nutrition interventions are consistently identified as one of the most cost-effective development actions, with significant economic returns”.

The 2020 review found that DFID’s practice of combining nutrition-specific support with nutrition-sensitive programming was well aligned with evidence on ‘what works’. It warned, however, that “continued prioritisation of nutrition investments and systems building is needed to capitalise on the positive progress”. The review noted that globally, progress towards reducing undernutrition in the poorest countries was stalling, and that COVID-19 had further hampered efforts to reach Sustainable Development Goal 2’s commitment to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

The follow-up of the recommendations from the 2020 nutrition review was mainly positive, highlighting the development of valuable new guidance to strengthen the design and targeting of nutrition interventions, results systems and strategic approaches. The follow-up review noted that the next step was for FCDO to prioritise implementing these new approaches.

ICAI has not conducted another nutrition review since then, but its 2023 review of UK aid to agriculture in a time of climate change included nutrition-sensitive agriculture among its themes. One of its review questions asked if “the UK’s support for agriculture is achieving its intended outcomes on inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction, food and nutrition security and climate change”. The review found that attention to the nutrition sensitivity of relevant programming had waned and that, towards the end of the review period, “scaling back and cancelling programmes negatively affected the [agriculture] portfolio’s ability to deliver against intentions. ODA reductions also made it more difficult to focus on cross-cutting priorities such as nutrition, gender, climate change and MEL [monitoring, evaluation and learning]”.

While the 2023 review found modest improvements in the agriculture portfolio’s inclusion of nutrition, it found insufficient attention to monitoring nutritional outcomes, especially in commercial agriculture programmes, with limited attention to the nutritional impact on consumers. Some relevant programmes had no references to nutrition, while others made assumptions of nutrition relevance that were not substantiated. The team found aid-funded agriculture investments in Malawi that had the potential to affect the nutrition of consumers negatively. As a result, ICAI recommended that all commercial agriculture programmes and investments should be monitored for nutritional outcomes. The government accepted ICAI’s recommendation.

This year’s follow-up review finds that, since the publication of ICAI’s review of UK aid to agriculture, high-level interest and commitment to nutrition have grown. The government has taken positive steps to reinvigorate the UK’s influence and thought leadership on agriculture and nutrition, including its leadership in the Global Summit on Food Security held in November 2023, with the UK prime minister, foreign secretary and minister for Africa and development attending. The November 2023 White Paper on International Development, presented at the summit, has a new focus on food and nutrition security.

FCDO has undertaken relevant actions to improve monitoring of the nutrition relevance of its portfolio, some of which build on previous recommendations in ICAI’s earlier 2020 review Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition. With the introduction of a nutrition policy marker in 2022, FCDO is now more aware of the reach of its nutrition-relevant programming, which has helped the nutrition team to reach out to programmes and provide advice.

Together, the high-level commitment and programme-level monitoring have helped facilitate and improve the FCDO nutrition team’s engagement with agricultural teams and their programmes, leading to improvements in the integration and tracking of nutritional outcomes, especially in commercial agricultural programmes. However, negative impacts will not be monitored by FCDO and BII will not be monitoring its nutrition impacts, positive or negative.

4. Findings from individual follow-ups

4.1 This section presents the results of our follow-up assessments of the government’s responses to ICAI’s recommendations. Each review we have followed up on is presented individually, with a focus on the most significant results and gaps in the government response. We begin by presenting the findings for the reviews we are following up on for the first time since their publication. For each review, we assess government progress recommendation by recommendation, before summing up and scoring the overall response to ICAI’s recommendations as adequate or inadequate. We then turn to the four reviews with outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up process. For outstanding issues, since we usually do not revisit entire past reviews and instead only some recommendations, we score each recommendation individually and make a decision on whether we will return to each recommendation again next year.

Transparency in UK aid

There has been a positive change in FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency, supported at ministerial and senior management level and promoted by a strengthened transparency team. There is stronger staff appreciation of the importance of transparency for FCDO’s development work. Systems integration, while not fully completed, now allows automatic publication of some key aid programme data (although not yet business cases and annual reports), and transparency work has become easier and less time-consuming for staff. Guidance has been clarified and training has been stepped up. FCDO looks to be on track to achieve a rating of ‘very good’ in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index.

management level and promoted by a strengthened transparency team. There is stronger staff appreciation of the importance of transparency for FCDO’s development work. Systems integration, while not fully completed, now allows automatic publication of some key aid programme data (although not yet business cases and annual reports), and transparency work has become easier and less time-consuming for staff. Guidance has been clarified and training has been stepped up. FCDO looks to be on track to achieve a rating of ‘very good’ in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index.

While FCDO needs to continue the same trajectory to reach its ambition to regain its global leadership role in aid transparency, its improvements are significant. The department does, however, need to support its arm’s-length bodies and other government departments to raise their aid transparency ambitions. This would include support to make publication of aid data to International Aid Transparency Initiative standards easier through, for example, improving the accessibility of DevTracker for non-FCDO users.

4.2 ICAI’s rapid review of Transparency in UK aid was published in October 2022. The review found that the UK had been a global leader on aid transparency since the late 2000s and that the former Department for International Development (DFID) had been a strong supporter of the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) and its development of a global standard for publishing aid data. Indeed, the establishment of ICAI in 2010 was part of this drive towards transparency in how UK aid money was spent. However, the merger in 2020 of DFID with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) was followed by a period in which the UK’s commitment to aid transparency came into question, including very little transparency around the aid budget reductions in 2020 and 2021 and a drop in ranking on the Aid Transparency Index (ATI) from ‘very good’ for DFID in 2020 to ‘good’ for FCDO in 2022. In January 2023, ICAI’s review of The UK’s approach to democracy and human rights found that the UK was “at risk of being declared an ‘inactive’ member by the Open Government Partnership, a coalition of 77 countries which assists governments in becoming more transparent, accountable and responsive”, with reduced transparency commitments among the issues raised. It appeared that the issue of reduction in transparency was not confined to the aid sector.

4.3 Concerned about this decline, ICAI noted that transparency was key to high-quality, principled development assistance, and provided four recommendations to support FCDO to build on previous UK efforts and continue to aim for high standards in aid transparency.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| FCDO should set out clear and ambitious standards for transparency to be applied to all aid portfolios (including arm’s-length bodies) through its unified systems, including default and timely publication of full programme documents, and a rigorous process for assessing, approving and reporting on exclusions. | Accepted |

| FCDO should commit to achieving a standard of ‘very good’ in the Aid Transparency Index by 2024. | Accepted |

| FCDO should resume publishing forward aid spending plans, cross-departmental development results and country aid priorities. | Accepted |

| In FCDO priority countries, the department should work with other donors to support greater use of IATI data and other aid information sources, to strengthen aid effectiveness and accountability. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: FCDO should set out clear and ambitious standards for transparency to be applied to all aid portfolios (including arm’s-length bodies) through its unified systems, including default and timely publication of full programme documents, and a rigorous process for assessing, approving and reporting on exclusions.

4.4 ICAI found that there were different values, cultures and technical capacities on transparency within former DFID and FCO, with a weakening of the presumption of disclosure – that is, that the default should be to publish rather than withhold data – in the newly formed FCDO. FCDO’s publishing of aid data became significantly less timely and complete compared to that of DFID, and arm’s-length bodies which had previously been linked to FCO, such as the British Council, had weaker publication standards. The same was the case with the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment (BII).

4.5 FCDO accepted ICAI’s recommendation and committed to having one unified system to “allow for a unified transparency process including putting in place the systems to assess, approve and collate information relating to exclusions of official development assistance (ODA) programme data, a proportionate approvals process for publishing, systematic and timely publication of programme documents”. Even though there are some remaining challenges, in the past year the department has come a long way in re-establishing the strong transparency practices of DFID:

- High ambition: The November 2023 White Paper on International Development brought transparency to the fore and returned to the ambition that “the UK will take a lead in promoting aid transparency internationally”. The white paper committed FCDO to becoming the foreign ministry with the highest transparency standards globally and “BII to become the most transparent of all bilateral development finance institutions”, as measured by Publish What You Fund (PWYF) transparency indexes.

- Clear standards: FCDO’s updated Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) has transparency as a key principle, since “British taxpayers, beneficiaries, and constituents in the countries where we operate have a right to know what we’re doing, why and how we’re doing it, how much it will cost and what it will achieve”. There is a separate PrOF rule on aid transparency (rule 7), but the PrOF also refers prominently to the importance of transparency across a range of other rules.20

- Default and timely publication: This is again the norm for FCDO programme documents. As of 28 June 2023, FCDO resumed monthly publication of aid programme data to IATI and Development Tracker (DevTracker), FCDO’s public aid information portal. FCDO’s internal Aid Management Platform (AMP) is linked to DevTracker so that relevant programme data on AMP, such as budgets, are automatically published on DevTracker, although business cases and annual reports are not yet managed or published through AMP. As a result, DevTracker is re-establishing itself as a go-to resource for UK aid data, after a period of pauses and gaps in publication undermining its reliability.

- Rigorous process for exclusions: The updated PrOF makes clear that sensitivities in programme documentation must be identified early by the programme responsible owner (PRO) and any exclusions from publication must be justified by the PRO and approved by the senior responsible owner, who is accountable for ensuring that the PrOF transparency standards are met. The default is thus to publish, and to exclude documentation from publication entails going through a thorough process of justification and approval.

4.6 While these are considerable steps towards re-establishing high standards of aid transparency, not all FCDO staff have access to operate the live version of AMP, which means they are unable to publish automatically to DevTracker. This continues to affect many former FCO staff, and the slow IT rollout is hampering FCDO’s aid transparency ambitions.

4.7 The situation is less positive for arm’s-length bodies, BII and other government departments. DevTracker is linked to AMP but is not as compatible with the systems of non-FCDO departments or bodies. For instance, the British Council continues to have an erratic publication record. FCDO’s transparency team recently (February 2024) uploaded FCDO’s data pertaining to its aid support of the British Council until December 2023 to DevTracker. This had to be done manually, however, which is cumbersome, and the British Council’s own ODA data have not been uploaded. While we appreciate that some records are now updated to December 2023, there is currently no solution in place for ensuring that FCDO’s arm’s-length bodies publish timely and regular ODA data.

4.8 BII published a transparency roadmap in December 2023, setting out its plans for becoming the most transparent bilateral development finance institution. This is a positive step, but it is too early to assess how well this roadmap will be followed or what impact it will have. The roadmap commits BII to report to IATI on a quarterly basis, and we have been told that BII has appointed a new Transparency Officer. As of April 2024, BII last published its data on 12 March 2024, but without any financial data for October-December 2023. IATI currently records BII as having a time lag in its data of one year. In our follow-up of the India country portfolio review this year, we note concern about the openness of BII when it comes to describing the details of intermediated investments in India.

4.9 In the case of other government departments, FCDOs transparency team is leading a cross-government transparency community of practice and has also led the work on agreeing the transparency commitments in the National Action Plan for Open Government 2024-26 (also known as NAP 6). However, the aid transparency commitments from departments other than FCDO are unambitious, and data are often outdated on DevTracker. For example, there are no data after financial year 2019-20 for the Home Office or Ministry of Defence, and no data after financial year 2021-22 for HM Treasury. FCDO is currently the only UK aid-spending department that PWYF includes in the ATI.

4.10 To conclude, while there are improvements, significant barriers remain for arm’s-length bodies and other government departments which are not using FCDO’s AMP to publish aid data in a timely and predictable manner. However, FCDO’s own achievements have been considerable. We therefore assess progress on this recommendation to be adequate.

Recommendation 2: FCDO should commit to achieving a standard of ‘very good’ in the Aid Transparency Index by 2024.

4.11 In 2022, FCDO was rated ‘good’ on the ATI, compared to DFID’s ‘very good’ rating in 2020, before the ICAI noted that if FCDO remained at that level it would send the wrong signal about the UK’s commitment to aid transparency. FCDO accepted the recommendation that it should commit to achieving a standard of ‘very good’ in the 2024 index. This commitment was repeated by the minister of state for development and Africa to Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC).

4.12 As part of the follow-up review, ICAI conducted a ‘test run’ of FCDO’s DevTracker data against the Publish What You Fund methodology underpinning the ATI. We found that FCDO is on track to achieve a ‘very good’ score. As discussed under recommendation 1, programme data are published monthly, and forward-looking disaggregated budgets and country development partnership summaries have also been published. We were not able to check the extent to which documents are correctly ‘tagged’ – or that irrelevant documents are not ‘over-tagged’ – but we noted that FCDO’s transparency team is aware of the importance of carefully reviewing tagging practices to avoid failing PWYF’s manual sampling checks. Further learning from ICAI’s ‘test run’ was shared with the transparency team to support their work of strengthening the department’s publication practice.

4.13 While the 2024 ATI rating had not yet been revealed by the time this follow-up review was published, the efforts across FCDO to improve the department’s transparency practice have been considerable and the department has shown it is strongly committed to achieving a ‘very good’ score. We therefore assess the response to this recommendation to be adequate.

Recommendation 3: FCDO should resume publishing forward aid spending plans, cross-departmental development results and country aid priorities.

4.14 ICAI’s original review found that FCDO’s forward spending plans had been untransparent ever since the merger. Country development plans and forward country budget information for UK aid programmes in partner countries were not available, making it difficult for partner governments to undertake their own resource planning, and for Parliament and civil society to scrutinise UK aid spending. FCDO accepted the recommendation to resume the publication of forward aid spending plans, cross-departmental development results and country aid priorities.

4.15 ICAI’s concerns were largely addressed by the publication in July 2023 of the FCDO annual report and accounts, which included planned ODA allocations for 2023-24 and 2024-25, split by country. FCDO has also published country development partnership summaries (CDPSs) for almost all countries with a minimum £5 million UK bilateral ODA spend. There are currently 43 CDPSs published, with budgets for 2023-24 and indicative budgets for 2024-25.

4.16 There has been less improvement on publishing cross-departmental development results. The original government response to ICAI’s recommendations was that “FCDO is in the process of developing the monitoring framework for the international development strategy. This will complement the high-level departmental results published in the outcome delivery plan”, published in July 2021 to cover the financial year 2021-22.24 A new outcome delivery plan was planned for publication in 2023, later changed to 2023-24, and has not yet been published. The 2023 annual report and accounts provides narrative accounts of results around the world reported against its four priority outcomes (of which outcome 3 is aid-related). These priority outcomes are broadly phrased: not results reporting as such (against baselines and towards targets), but a list of activities and achievements within the broad ODA-related objective to “promote Global Britain by using our development leadership to empower and protect the freedom of women and girls, to provide reliable, honest infrastructure financing, and to support humanitarian needs”.

4.17 Through the publication of forward allocations and CDPSs, FCDO has addressed the key concerns underpinning ICAI’s recommendation. The response to this recommendation is therefore judged to be adequate. We nevertheless would like to see further improvements in the form of longer-term indicative budget information available to partners (governments and civil society) in priority countries. The indicative forward budgets provided in the CDPSs are useful for partners, but they only cover the financial year that started in April 2024. We also note that there has been slow progress on reporting cross-departmental development results.

Recommendation 4: In FCDO priority countries, the department should work with other donors to support greater use of IATI data and other aid information sources, to strengthen aid effectiveness and accountability.

4.18 ICAI’s review found that, in general, efforts to promote and facilitate the use of IATI and other aid data to strengthen aid effectiveness and accountability have been limited. Specifically for FCDO, it found that the department could do more to promote the use of the aid data it and other donors gather in priority countries. FCDO accepted the recommendation and listed a range of actions to improve aid data use which are currently underway.

4.19 The follow-up found that, at a global level, FCDO is engaging more strongly with IATI. It has joined the new IATI data use working group, convened IATI donor coordination meetings and chaired the donor caucus at the IATI 2023 members’ assembly. FCDO is working with the Open Government Partnership initiative at both international and domestic levels, including leading on the government’s aid transparency commitment in NAP 6 which includes FCDO commitments to continue to improve aid data quality and timeliness, strengthen engagement with IATI users and champion aid transparency improvements globally. There is already evidence that FCDO is pursuing these aims. First of all, it has reinstated automatic publication to DevTracker and monthly publishing to IATI, which is the starting point of encouraging stronger usage of aid data. It has also worked on the DevTracker website to make it more user-friendly. The improvements to DevTracker appear to focus particularly on bringing the platform in line with government digital service requirements in terms of accessibility. FCDO makes the source code for DevTracker available on GitHub, a developer platform for code sharing and storing, making it easy for others to validate the department’s report on progress in accessibility.

4.20 In partner countries, positive change is at a relatively early stage, but relevant actions are underway. It was reasonable of FCDO to focus first on the actions necessary to achieve its ambition of ‘very good’ in the 2024 ATI, since improving use of aid data at country level is dependent on first improving the quality of the information FCDO is publishing (see recommendation 1 on this). It is also supported by FCDO’s increasing engagement with the IATI secretariat and donor community at policy level.

4.21 An interview with staff at the British High Commission in Abuja, Nigeria, made it clear that with the resumption of regular updates of DevTracker, it has become easier to use aid data to improve efficiency and coherence internally at the high commission. With a common live repository of data on aid programmes, it is simpler and less time-consuming to map what other teams are doing, which improves country planning and reduces overlap. In working with governments and civil society organisation (CSO) partners, it is now possible to signpost to DevTracker again, as well as to the published country development partnership summaries.

4.22 There is much more to be done to increase data use at country level, and it will be important for FCDO to continue to maintain its ambition. FCDO should contribute to an evolving understanding of the specific mechanisms required for transparency to lead to aid effectiveness and, where relevant, contribute to overcoming barriers to the use of information. Due to sequencing of work and the positive direction of travel, combined with the strong commitment within FCDO to continue improving, we find that actions have been adequate. However, following the systems integration, and after the end of data collection for the ATI in 2024, FCDO should redouble its efforts on this recommendation. Strengthening use of data at country level is likely to lead to significant benefits in terms of improving value for money and increasing impact of UK aid.

Conclusion

4.23 There has been a positive change in FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency, driven at ministerial and senior management level and promoted by a strengthened transparency team. The transparency team told ICAI that they noted a cultural change taking place within the department, with staff appreciating the importance of transparency for FCDO’s development work. This cultural change is supported by the systems integration allowing automatic publication, which is making transparency work easier and less time-consuming. Guidance and training have also been stepped up. While improvements need to continue on the same trajectory to reach FCDO’s ambition to regain its global leadership role in aid transparency, ICAI is pleased to find that the response to all of its recommendations has been adequate. It will become increasingly important for FCDO to support its arm’s-length bodies as well as other government departments to raise their aid transparency ambitions. This would include support to make publication of aid data to IATI standards easier through, for example, improving the accessibility of DevTracker for non-FCDO users.

UK aid to Afghanistan

There is evidence of learning activities and progress across the three recommendations of ICAI’s report, particularly regarding FCDO’s improved use of scenario planning. The department is putting in place new guidance and mechanisms for learning about its work in fragile and conflict-affected settings, with the aim, among other things, of mitigating the risk of repeating the mistakes ICAI identified in Afghanistan. The mechanisms for internal challenge are visibly stronger, showing that the recommendations of the Chilcot Inquiry, conducted after the Iraq war, still have currency and relevance seven years after their publication. ICAI continues to take the view that the use of ODA to pay the salaries of police officers deployed on paramilitary tasks amounts to an inappropriate use of ODA to fund paramilitary operations.

regarding FCDO’s improved use of scenario planning. The department is putting in place new guidance and mechanisms for learning about its work in fragile and conflict-affected settings, with the aim, among other things, of mitigating the risk of repeating the mistakes ICAI identified in Afghanistan. The mechanisms for internal challenge are visibly stronger, showing that the recommendations of the Chilcot Inquiry, conducted after the Iraq war, still have currency and relevance seven years after their publication. ICAI continues to take the view that the use of ODA to pay the salaries of police officers deployed on paramilitary tasks amounts to an inappropriate use of ODA to fund paramilitary operations.

4.24 ICAI’s country portfolio review of UK aid to Afghanistan, published in November 2022, looked at UK aid aimed at stabilising Afghanistan and building a functional state. The review found that although UK aid had provided valuable support to Afghan citizens, including women and girls, the UK did not have a realistic or credible approach to state-building and failed to make substantial progress towards this strategic objective. The review was scored amber-red.

4.25 The review offered three recommendations aimed at ensuring that lessons from Afghanistan can inform future stabilisation efforts in other contexts. The follow-up of this review focuses on such broader learning efforts, while a separate information note on humanitarian aid to Afghanistan since May 2023 will be published by ICAI in June 2024. This forthcoming information note will be an update on the information note on UK aid to Afghanistan published in May 2023.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| In complex stabilisation missions, large-scale financial support for the state should only be provided in the context of a viable and inclusive political settlement, when there are reasonable prospects of a sustained transition out of conflict. | Partially accepted |

| UK aid should not be used to fund police or other security agencies to engage in paramilitary operations, as this entails unacceptable risks of doing harm. Any support for civilian security agencies should focus on providing security and justice to the public. | Accepted |

| In highly fragile contexts, the UK should use scenario planning more systematically, to inform spending levels and programming choices. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: In complex stabilisation missions, large-scale financial support for the state should only be provided in the context of a viable and inclusive political settlement, when there are reasonable prospects of a sustained transition out of conflict.