UK aid to refugees in the UK: ODA eligibility update

1. Introduction

1.1 Under international aid rules, some of the costs of supporting refugees and asylum seekers in the first year after their arrival in the UK count as official development assistance (ODA). This category of aid is referred to as ‘in-donor refugee costs’. The rationale is that supporting refugees with basic services and accommodation is a form of humanitarian assistance, wherever they are located. ICAI’s March 2023 rapid review, UK aid to refugees in the UK, found that the exponential rise of in-donor refugee costs since 2020, to £3.7 billion or almost a third of the total aid budget in 2022, has had a serious impact on UK aid as a whole, and represented poor value for money for taxpayers.

1.2 By far the largest cost was to cover the Home Office’s use of hotels as accommodation for asylum seekers, which alone amounted to almost £1.9 billion of ODA in 2022. The total amount of in-donor refugee costs reported by the Home Office for 2022 was almost £2.4 billion, covering accommodation and support for asylum seekers, resettled refugees, victims of modern slavery, and Afghans arriving on the Afghan Citizen Resettlement Scheme. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities was the second-largest ODA spender on in-donor refugee costs, with £524 million on the Homes for Ukraine scheme. Other departments also reported steep increases in ODA spending: in 2022 the Department for Education spent £216 million of ODA in this category, the Department of Health and Social Care £274 million, the Department for Work and Pensions £160 million, and HM Revenue and Customs £21 million. In addition, £109 million incurred by the devolved administrations was reported as ODA.

1.3 ICAI found that the government’s decision to allow an unlimited share of the aid budget to be spent on in-donor refugee costs undermined incentives for longer-term planning on how to accommodate refugees and asylum seekers, and noted that the Home Office was not effectively overseeing the value for money of these services. The government’s decision also wreaked havoc with the aid programme managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), which had to make dramatic reductions, taking support away from populations in crisis in developing countries. Furthermore, the unpredictability of the Home Office’s ODA spending undermined FCDO’s budget predictability and forward planning.

1.4 The UK government’s Illegal Migration Act (from here on ‘the Act’), which received royal assent on 20 July 2023,3 is an important development in relation to in-donor refugee costs. The Act bars most people arriving by irregular means from receiving asylum in the UK, and provides for them to be detained and deported instead. Based on ICAI’s assessment, the Act, if implemented as drafted, would impact the UK’s ability to report as ODA any spending on people arriving irregularly in the UK with the aim of seeking asylum. The purpose of this update is to examine, to the extent possible given ongoing uncertainty around the Act’s implementation, the potential impact on the UK aid budget. It does so through a review of the Act against international ODA eligibility criteria and the UK’s methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs. As ICAI’s remit is limited to ODA expenditure, it is not the intention of this update to comment on UK asylum or refugee policy. ICAI has not sought legal advice on the Act.

1.5 The update is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a brief description of the Act, while Section 3 assesses ODA eligibility issues raised by the Act with reference to the international ODA reporting criteria developed by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and the UK’s own methodology for how it reports in-donor refugee costs. Section 4 sets out three brief illustrations of how the volume of in-donor refugee costs reported as aid could be affected by the Act once it commences.

1.6 The update will help the International Development Committee, other parliamentarians and other stakeholders, as well as the UK government itself, to understand the implications of the Act for how government departments will spend ODA on in-donor refugee costs, and particularly for how the Home Office will finance accommodation and support to people arriving in the UK by irregular means who wish to seek asylum in the UK.

Box 1: Trends in asylum arrivals, processing and accommodation

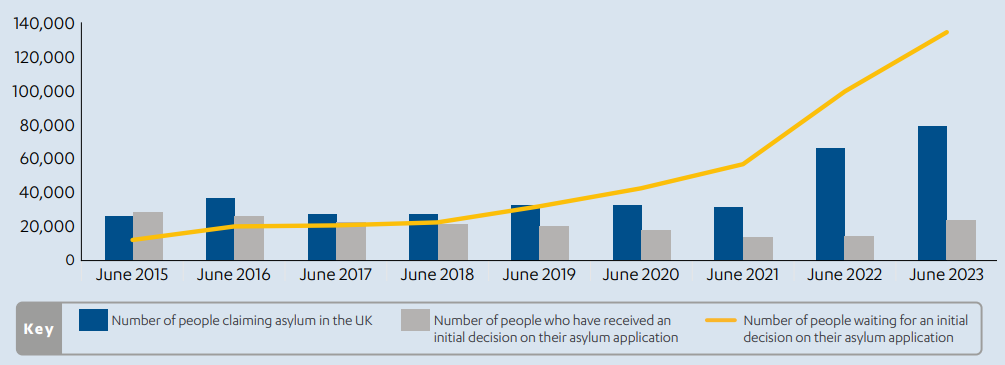

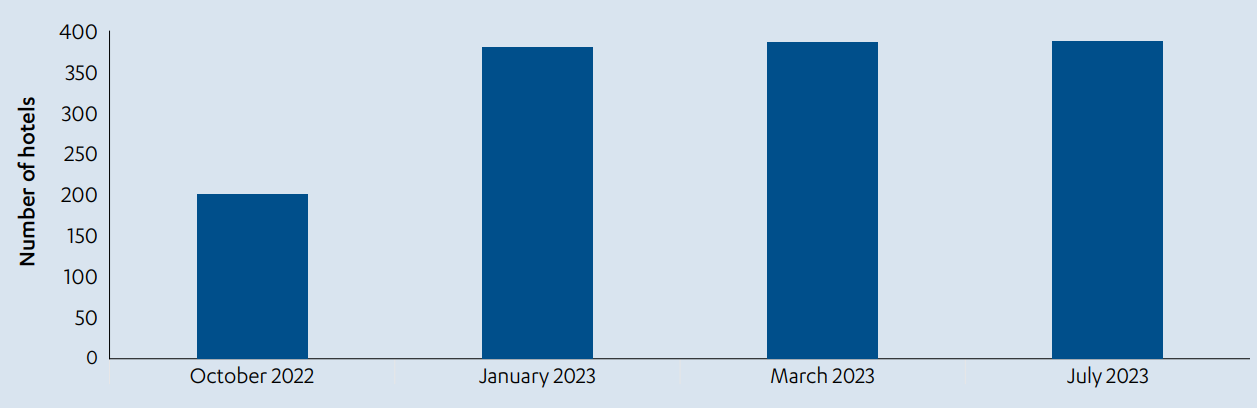

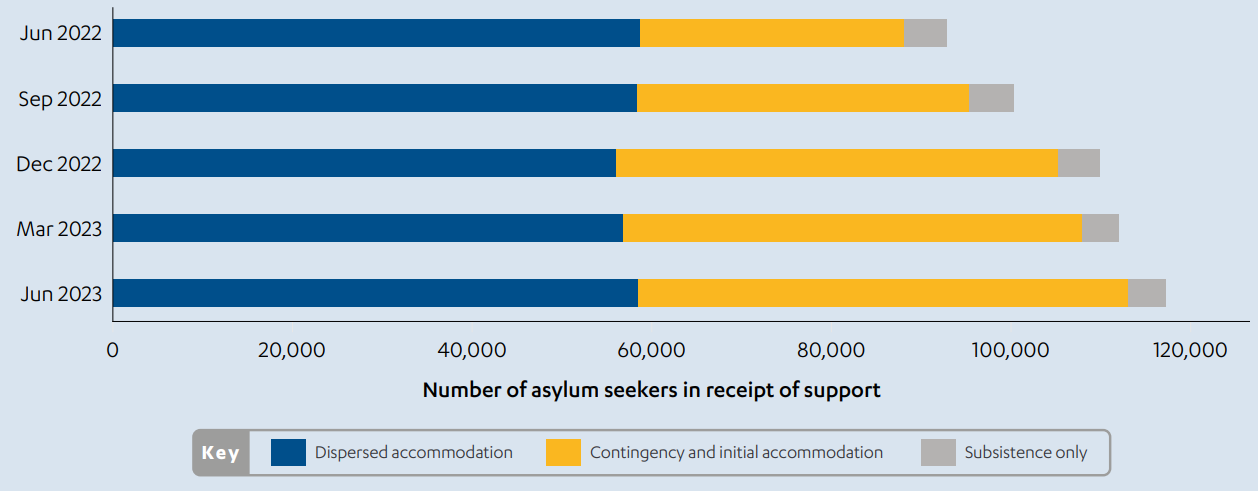

Recent trends in Home Office data show that the size of the asylum decision backlog continues to rise, as the number of new applicants outstrips the increase in asylum decisions made (Figure 1). The use of hotels as contingency accommodation for asylum seekers increased marginally in the first half of 2023 (Figure 2). There is little change in the use of contingency accommodation (mainly hotels) as a proportion of all housing for asylum seekers during the past 12 months (Figure 3)

Figure 1: The size of the asylum decision backlog, 2015-23

Data are for main applicants and do not include dependants. Cases waiting for an initial decision are asylum applications lodged since 1 April 2006 which are still under consideration.

Source: Asylum applications awaiting decisions dataset, June 2023, accessed from Asylum and resettlement datasets, Home Office, August 2023, link (accessed August 2023).

Figure 2: Trends in hotel use as contingency accommodation for asylum seekers

Note on sources: October 2022 and March 2023 figures are from UK aid to refugees in the UK, Independent Commission for Aid Impact, March 2023, p. 21, link, while the January and July figures were provided to ICAI in written evidence from the Home Office on 10 August 2023.

Figure 3: Trends in types of support for asylum seekers, June 2022 to June 2023

Figure 3 includes ODA and non-ODA spend on all types of contingency, initial and dispersed accommodation as well as subsistence-only support for destitute asylum seekers awaiting the outcome of their asylum claim. Dispersed accommodation is temporary accommodation used on a longer-term basis, for example houses or flats managed by the Home Office, while asylum applications are being processed. Contingency and initial accommodation is usually hostels or hotels, provided until dispersed accommodation can be sourced.

Source: Asylum seekers in receipt of support, by support type, June 2023, accessed from Asylum and resettlement datasets, Home Office, August 2023, link (accessed August 2023).

2. What is the Illegal Migration Act?

2.1 The Illegal Migration Bill was introduced to Parliament on 7 March 2023. It received royal assent on 20 July 2023, after lengthy deliberations in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The main elements of the Act, as relevant to individuals’ ability to receive asylum and refugee protection in the UK and how they are treated, are set out below (anything in quotation marks is directly from the Act, with relevant paragraph numbers in parentheses).

2.2 Purpose: The purpose of the Act is to make provisions for the removal of anyone arriving in the UK “in breach of immigration control”, by returning them to their home country or to a safe third country where their asylum or human rights claim can be assessed. The Act describes the removal requirement as aimed at preventing “unlawful migration, and in particular migration by unsafe and illegal routes” (1(1)). It should be noted that the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) does not use the term ‘unlawful’ or ‘illegal’ in relation to asylum seekers, since the 1951 UN Refugee Convention specifically notes that the manner of an asylum seeker’s arrival does not affect their ability to seek protection. According to UNHCR, the Convention “recognises that the seeking of asylum can require refugees to breach immigration rules”.

2.3 The Home Office’s explanatory note accompanying the Act describes the Act’s objectives as to: deter illegal entry into the UK; break the business model of people smugglers and save lives; promptly remove those with no legal right to remain in the UK; and make provisions for an annual cap on the number of people to be admitted to the UK through safe and legal routes.

2.4 Scope of application: Section 2 of the Act sets out four conditions for removal. If a person arriving in the UK meets these conditions, the Secretary of State has a duty to remove them from the UK. Paraphrased, the four conditions are: the person has (i) arrived in the UK in breach of immigration rules; (ii) done so on or after the day the Act was passed; (iii) not come to the UK directly from a country where their life and liberty were threatened by reason of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion; and (iv) requires, but does not have, leave to enter or remain in the UK, including for the sake of seeking asylum.

2.5 Some exceptions are made to the removal requirement for unaccompanied children and victims of modern slavery.

2.6 Measures: The Act aims to achieve these objectives through the following measures:

- The Secretary of State’s duty to remove from the UK people falling under the four conditions described above.

- A requirement to detain people whom immigration officers deem to have arrived illegally, until a decision is made on whether there is a duty to remove an individual, and also pending removal once that decision has been made.

- The Secretary of State’s duty to provide an annual capped number for entrants using safe and legal routes to the UK. The Secretary of State is also required to report to Parliament within six months of the Act being passed on what safe and legal routes exist for people who would fit the refugee definition or are otherwise eligible for protection.

2.7 Commencement: The Act and the explanatory note state that the Act applies to people arriving illegally in the UK from the day the Act is passed. Some elements came into force on 20 July, while others will be brought into force at a later date through “commencement regulations made by the Secretary of State” (68(1)). However, in written evidence to ICAI on 10 August 2023, the Home Office stated that it had not used any powers under the Illegal Migration Act with regards to inadmissibility and detention, as the relevant powers have not yet commenced.

3. How does the Act affect the reporting of in-donor refugee costs as ODA?

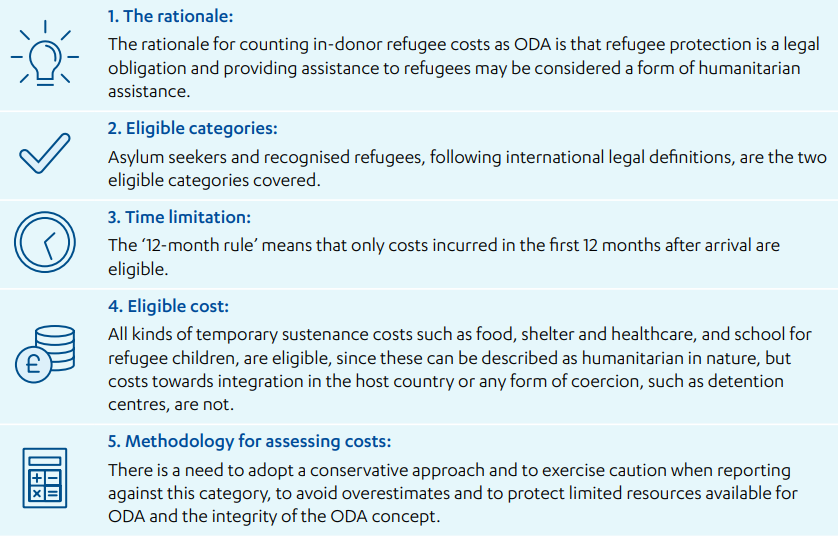

3.1 International aid reporting rules stipulate that services provided to asylum seekers and refugees in the first 12 months after their arrival in donor countries can be reported as ODA if they are of a humanitarian nature and cater to immediate basic needs, rather than longer-term integration. To be ODA-eligible, activities must not include denial of freedom of movement, detention or involuntary removal. Table 1 below sets out five clarifications from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) on what donor countries are allowed to report as aid spending on in-donor refugee costs. The clarifications understand an asylum seeker as “a person who has applied for asylum and is awaiting a decision on status”. For a thorough explanation of the DAC rules, please see Section 3 of the original ICAI rapid review.

Table 1: The five DAC clarifications on reporting in-donor refugee costs

3.2 Soon after the Act received royal assent, a spokesperson for the DAC Secretariat, when asked about the implications for ODA eligibility of costs if asylum seekers arriving irregularly are barred by the Act from receiving asylum in the UK, commented: “The rules indicate such costs could not be counted as ODA, but the OECD has yet to examine the bill in more detail and confirm its position”. The rest of this section sets out ICAI’s assessment of the relevance of the Act for how the UK reports against each of the five rules established by the DAC. The assessment is based on a close reading of the DAC clarifications, but it is important to note that the DAC has not yet been asked by the UK government to advise on the ODA eligibility elements of the Act and has not yet provided a confirmed opinion. ICAI’s assessment is that, if all sections of the Illegal Migration Act are implemented, various categories of expenditure that were previously reported as ODA would no longer be eligible. This would significantly reduce the share of UK aid spent as in-donor refugee costs, unless the government were to increase opportunities for safe and legal resettlement to the UK considerably, which does not appear to be envisaged in the Act.

3.3 With the DAC clarifications in Table 1 in mind, the Illegal Migration Act potentially affects the ODA eligibility of UK spending on refugees and asylum seekers in three main ways:

- ODA-eligible rationale: by affecting the humanitarian nature of the spending and the legal obligation of the UK to provide protection to refugees.

- ODA-eligible categories of people: by limiting who is allowed to receive asylum or refugee status in the UK and is thus eligible for ODA-funded support.

- ODA-eligible activities: due to the Act’s emphasis on detention, removal and other coercive activities, by affecting to what extent accommodation and support services for people who arrive in the UK to seek asylum can be financed with UK aid.

Rationale

3.4 The humanitarian rationale for reporting in-donor refugee costs as aid is strongly affected by the Act. The Act has been subject to comment by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. They found that the Act “is at variance with the country’s obligations under international human rights and refugee law and will have profound consequences for people in need of international protection” and “will exacerbate the already vulnerable situation of people who arrive irregularly in the UK, drastically limiting the enjoyment of their human rights, and putting them at risk of detention and destitution”. This has implications for whether expenditure under the Act can fairly be described as humanitarian in nature and in support of the UK’s legal protection responsibilities.

3.5 In its explanatory note accompanying the Act, the Home Office expresses the government’s objective that people will only seek protection in the UK through safe and legal routes. If this were to lead to higher levels of refugee resettlement, then the part of the Act concerning safe and legal routes would appear to fall within a humanitarian rationale. However, while the explanatory note mentions the Prime Minister’s promise to “create more of those routes”, the Act itself only requires the government to set an annual maximum cap on, and report to Parliament on the availability of, safe and legal routes. There is no minimum level at which the cap should be set, and the Prime Minister has stated that: “we can only […] implement those routes once we have proper control of our borders. That is what we must deliver first”.

3.6 The majority of people who have received some form of protection in the UK through safe and legal routes have arrived on nationality-based schemes (notably for Hong Kong and Ukrainian nationals, but also limited schemes for some Afghan and Syrian refugees). Such schemes have created tailored pathways to protection in the UK for many individuals, but an implication of this nationalities-based approach is that most nationalities do not have a dedicated scheme and thus have no safe and legal route through which to seek asylum in the UK. According to Home Office data, 183,600 Ukraine scheme visa holders were in the UK as of 7 August 2023, while 113,500 visa holders on the Hong Kong British National (Overseas) scheme had arrived in the UK by the end of March 2023. The total of these two categories of visa holders represents about 60% of the around 500,000 people who have received some form of protection in the UK since 2015.

Eligible people

3.7 There is no asylum visa to enter the UK. Unless from a country with visa-free access to the UK, the only way to seek asylum in the UK is by arriving irregularly, such as by small boats, or arriving on false documents or on a visa for a different purpose, such as a student visa or a tourist visa. The effect of the Act, if implemented, would be that individuals arriving irregularly or “in breach of immigration control”, as the Act states, are no longer entitled to protection by the UK as refugees or asylum seekers. In ICAI’s assessment, any spending on individuals who, due to their irregular arrival, are barred from receiving asylum in the UK, would therefore not meet the second of the OECD-DAC clarifications on in-donor refugee costs – which describes an asylum seeker as “a person who has applied for asylum and is awaiting a decision on status”. The Illegal Migration Act determines that the Secretary of State has a duty to remove anyone who fits the ‘four conditions for removal’ described in paragraph 2.4 above. This means that someone who meets the conditions for removal cannot truthfully be said to be “awaiting a decision on status” even if they apply for it, as their eligibility for receiving asylum in the UK has been ruled out by the Act due to their mode of arrival.

3.8 Currently, the largest part of the UK’s ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs is for accommodation and other support through the Home Office’s Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC), the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility contract (AIRE), and other contracts to provide accommodation and basic needs support for destitute people awaiting their asylum decision. If a person is deemed by the Home Office to fall under the four conditions for removal once the Act has commenced, then it is hard to see how spending related to that person under these contracts – or any other contract for initial, dispersed or contingency accommodation – would be ODA-eligible.

3.9 The Home Office confirmed to ICAI in writing on 10 August 2023 that it has not as yet used any powers under the Illegal Migration Act because the Act has not yet commenced. This means that there is currently no change in how asylum seekers arriving in the UK irregularly are categorised, and therefore no change in their ODA eligibility.

3.10 The Act will not affect ODA eligibility for the costs of resettling refugees in the UK through schemes such as the UK Resettlement Scheme. Nor will the Act impact on the UK’s ability to spend ODA on in-donor refugee costs for people arriving in the UK on tailored protection schemes – particularly Ukrainians arriving on the Homes for Ukraine visa scheme and Afghans on the Afghan Citizen Resettlement Scheme (ACRS).

Time limitation

3.11 In-donor refugee costs can only be reported as ODA in the first 12 months. The UK interprets this as “the date a [asylum] claimant applies for support”. Under this policy, if a person arriving irregularly to claim asylum is barred from receiving asylum in the UK by the Act, it is hard to see how they could be considered to be awaiting an asylum decision in the UK since their mode of arrival would automatically make their claim for protection in the UK inadmissible. Accordingly, the start of the 12-month eligibility period would not be triggered, and ODA funding would not be possible.

3.12 The Homes for Ukraine and ACRS schemes are not directly affected by the Act, but we are nevertheless likely to see a significant drop in aid funding for these schemes due to the 12-month rule. In the cases of both Homes for Ukraine and ACRS, recent data show that there has been a drop in new arrivals in 2023 (with ACRS there have hardly been any new arrivals). This means that aid costs to support Afghans and Ukrainians on these two schemes will taper off as the 12-month rule sets in during 2023.

Table 2: Arrivals on Homes for Ukraine scheme and ACRS, September 2021 to March/August 2023*

| Scheme | Arrivals (total since September 2021) | Arrivals 2023 (as of 31 March/8 August) |

|---|---|---|

| Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme (Homes for Ukraine) (as of 8 August 2023) | 119,000 | 9,100 |

| ACRS Pathway 1 (as of March 2023) | 9,059 | 3 |

| ACRS Pathway 2 (as of March 2023) | 40 | 18 |

| ACRS Pathway 3 (as of March 2023) | 14 | 14 |

| Total | 128,113 | 9,135 |

*This table only includes arrival data for those who have incurred ODA spend by the Home Office and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. Other government departments spend ODA on education, health and benefits for a broader group of Ukrainian and Afghan nationals who have arrived on visa schemes. See the original ICAI review, Section 3, for more detail.

3.13 A further potential complication for the 12-month rule is created by the inadmissibility process already in place, whereby asylum seekers arriving via third countries (such as France) first go through an assessment of whether their claim is admissible in the UK or they should be sent to a safe third country for their asylum claim to be processed there. This has meant an extra waiting period while the Home Office checks options for removal to third countries. When the government assesses its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs as ODA, it could consider whether it is in line with the DAC rules to count accommodation and support for people kept in the inadmissibility process holding pattern as ODA-eligible, or whether the 12-month rule should start from when the Home Office decides to begin to process a person’s application for asylum in the UK. ICAI recommended in its March 2023 review of UK aid to refugees in the UK that “the UK should revisit its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs, as Iceland did, with the aim of producing a more conservative approach to calculating and reporting costs”. The government rejected this recommendation but noted that “[d]etails of the methodologies used by spending departments will be published in a report prior to the publication of Statistics on International Development: Final UK aid spend 2022 in autumn 2023” and asserted that “[t]his report will demonstrate that the methodology is fit for purpose while highlighting areas for potential development”. This report is not yet published.

Eligible costs

3.14 Donors can report the provision of temporary services covering basic needs, such as shelter, food and children’s education, as aid. However, the DAC rules are clear that coercive activities, including detention, must be excluded. If the Act commences and its detention requirements are implemented, then services provided to individuals in detention facilities cannot be ODA-eligible. This may be a theoretical point, since if the Act is implemented in full, it would seem that those detained will not be in the asylum application system in the UK and would therefore not fall into an ODA-eligible category, but it is an important point of principle in the reporting criteria.

3.15 Involuntary return or removal to a third country are never ODA-eligible and can, as before, never be funded through the UK aid budget.

Conservative methodology

3.16 ICAI’s original review found that the UK’s method of calculating in-donor refugee costs could not be said to follow a conservative approach. It concluded that the “UK’s interpretations on what to include are generous, and the use of modelling based on unit costs rather than reporting actual costs risks over-reporting”. The UK government has not changed its methodology since ICAI’s March 2023 review, but has informed ICAI that the first meeting of the new UK Government ODA Board, which took place on 3 May 2023, discussed ODA-eligible in-donor refugee costs. While not providing any specifics, the government has informed ICAI that “the Board agreed tangible actions to better manage the predictability of in-donor refugee costs and its impact on the ODA budget. These actions are being taken forward by officials, overseen by a senior level group representing the Home Office, DLUHC [Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities], FCDO and HM Treasury”.

3.17 The government also confirmed to ICAI that the May 2023 Board did not address or make decisions relating to the impact of ODA eligibility on the passing of the Illegal Migration Act, but stated that “officials continue to work through the implementation and impacts of the Act”. ICAI had assumed that this would have been a topic for the ODA Board, considering the major questions that the implementation of the Act raises for ODA eligibility – as described in the paragraphs above.

3.18 In May 2023, following the release of the OECD’s preliminary ODA data for 2022, Carsten Staur, the Chair of the DAC, wrote a commentary noting that the “Secretariat has also encouraged DAC members to be conservative, whenever they make their assessments – not to overreport, but to act on the side of caution”. The OECD’s preliminary data for 2022 showed an average increase in the reporting of in-donor refugee costs from 4.6% in 2021 to 14.14% in 2022 of all ODA that year. The increase for all OECD-DAC countries was mainly due to the Ukrainian refugee crisis, although – as ICAI’s rapid review showed – in the UK the main reason for the country’s above-average increase was the Home Office’s use of hotel accommodation for asylum seekers. The DAC Chair stated that for donors’ 2023 ODA reporting it is clear that “[a]uthorities responsible for ODA reporting in each Member State capital must engage substantially with relevant national authorities – and colleagues in other DAC countries – to make sure that DAC rules are strictly applied, and that members take a cautious approach to the estimation of their in-donor refugee costs”. He further noted that “[e]ven though these costs can be reported as ODA, this does not mean that a country must do so”.

3.19 FCDO plans to publish detailed information on the UK methodology when it publishes its final statistics on international development for 2022 on 14 September 2023. The department notes that it will, in line with good practice, review and update the methodology if necessary. As recommended in ICAI’s original review, it is important that this is done with the aim of achieving a reporting approach that is conservative and cautious, in line with the fifth DAC clarification. But, even more fundamentally, the methodology needs to be in line with the DAC clarification that in-donor refugee support can be reported as ODA to the extent that it is humanitarian in nature and provided to refugees and asylum seekers as part of a legal obligation to provide protection.

4. Illustrations of how ODA could be affected in 2024

4.1 To illuminate the discussion in Section 3 above, we have set out three brief illustrative scenarios to give an idea of how the Illegal Migration Act, if commenced and its powers used, could affect the Home Office’s ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs for the calendar year 2024 (the first full year in which the Act could be commenced). These illustrations are not meant to provide any predictions, given the number of key uncertainties, not least how many asylum seekers and refugees will arrive and how the Act will be implemented – they are instead explanatory in nature. They are hypothetical scenarios, asking: “what would the UK’s ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs look like if taking the 2022 cost categories as the baseline but assuming that the Illegal Migration Act is commenced and implemented to different extents?”

4.2 The 2022 ODA spending by the Home Office (on asylum seekers and ACRS) and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (on the Homes for Ukraine scheme) is taken as the baseline for the scenarios. This spending was distributed according to the cost categories set out in Table 3 below, and the figures for 2022 are reproduced from ICAI’s original review. Table 3 sums up the hypothetical ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs by the two main ODA-spending departments, the Home Office and DLUHC, for each of the three scenarios, compared to 2022.

4.3 For the sake of setting out simple and clear scenarios, ODA reported as in-donor refugee costs for the Department for Education, the Department of Health and Social Care, the Department for Work and Pensions, HM Revenue and Customs and the devolved administrations is not included. This amounted to £780 million in 2022. Since this spend was mainly related to the Afghan and Ukrainian schemes, it is reasonable to anticipate that it would be significantly reduced for all three scenarios. We also do not attempt to calculate how many asylum seekers would still be having their applications assessed in the UK because their claims were lodged before the Act commenced, and are also still within the DAC clarification’s 12-month rule and thus eligible for ODA-funded assistance. While there would certainly be asylum seekers falling under this category in any 2024 scenario (as the first full year in which the Act could be implemented), we have for the sake of clarity and simplicity of the illustration not attempted to calculate this. The value of the scenarios is to show the vast difference in hypothetical ODA eligibility of the Home Office’s spend depending on how the Illegal Immigration Act is implemented, not to predict actual spend in 2024.

Illustrative scenario 1: Full Implementation

Main features of the Full Implementation scenario: Irregular arrivals at 2022 level; ODA costs for new arrivals on ACRS and Homes for Ukraine visa protection schemes reduced to 10% of 2022 figures (according to 2023 arrivals trend); the Act commenced and being fully implemented, but safe and legal routes not increased.

4.4 The Full Implementation scenario assumes the following:

- The same number of people arrive by irregular means in the UK with the aim to seek asylum as in 2022.

- The asylum determination backlog remains at about 130,000 main applicants awaiting a first decision.

- The Home Office’s reliance on hotels for contingency accommodation remains at around 380 hotel sites (or other contingency accommodation of similar per person cost).

- The numbers of people arriving on the Homes for Ukraine scheme and ACRS are significantly down, in line with the trend seen in data for quarters 1 and 2 of 2023, to 10% of 2022 levels.

- All elements of the Illegal Migration Act are commenced and are being implemented. This means that all new irregular arrivals falling under the Act’s four conditions are barred from having asylum claims assessed in the UK, and are placed in detention awaiting removal or deportation.

- The UK government has not managed to negotiate and implement enough agreements on return or transfer with third countries to match the number of people arriving.

- There are no direct routes for individual asylum seekers to travel to the UK to seek asylum without being in breach of immigration control (only nationality-based visa schemes).

- However, because irregular arrivals continue to be high, the UK government does not increase refugee resettlement places as a safe and legal route.

4.5 This illustrative scenario assumes that the situation in 2022 remains the same in 2024, in terms of the number of asylum seekers and resettled refugees arriving (but with a significant drop in arrivals on the Ukraine and ACRS visa protection schemes), the use of contingency accommodation and the size of the asylum decision backlog. The only difference is that the Act is implemented in full and irregular arrivals would be barred from having their asylum claims assessed in the UK. According to this scenario, the Home Office’s ODA spending on in-donor refugee costs would be sharply reduced compared to 2022, since most of the department’s spending would no longer be ODA-eligible, as can be seen in Table 3 below, column 3.

Illustrative scenario 2: Safe Routes

Main features of the Safe Routes scenario: Irregular arrivals at 2022 level; ODA costs for new arrivals on ACRS and Homes for Ukraine visa protection schemes reduced to 10% of 2022 figures (according to 2023 arrivals trend); the Act commenced and being fully implemented, but the Act’s objective to increase safe and legal routes is pursued.

4.6 The same assumptions are made for the Safe Routes scenario as for scenario 1, except for action undertaken on safe and legal routes. In scenario 2, the UK government aims to pursue all the objectives of the Act, including opening more safe and legal routes, by expanding the UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) to take 20,000 refugees per year.

4.7 The result for ODA costs can be seen in Table 3 below, column 4. The cost of resettlement for 20,000 refugees under the UKRS is extrapolated from 2022 UKRS ODA costs when 887 people were resettled under the scheme and £8 million in ODA costs were incurred. On this crude calculation, this would give an estimated ODA cost of around £9,000 per person.

Illustrative scenario 3: Partial Implementation

Main features of the Partial Implementation scenario: Partial implementation of the Illegal Migration Act, with ability to detain and deport constrained; Rwanda agreement commenced; irregular arrivals at 2022 level; new arrivals on ACRS and Homes for Ukraine scheme reduced (according to 2023 trend).

4.8 The Partial Implementation scenario assumes, in line with scenarios 1 and 2, that:

- The same number of people arrive by irregular means in the UK with the aim to seek asylum as in 2022.

- The asylum determination backlog remains at about 130,000 main applicants awaiting a first decision.

- The Home Office’s reliance on contingency accommodation remains at around 380 hotel sites (or other contingency accommodation of equivalent per person cost).

- The numbers of people arriving on the Homes for Ukraine scheme and ACRS are significantly down, in line with the trend seen in data for quarters 1 and 2 of 2023, to 10% of 2022 levels.

4.9 The Partial Implementation scenario differs from the two previous scenarios in assuming that the Act is only implemented for some irregular arrivals, not all. In this scenario:

- The Home Office’s five-year Rwanda agreement (the Migration and Economic Development Partnership with Rwanda) commences. The agreement stipulates that asylum seekers who have made a ‘dangerous and illegal journey’ to the UK are removed to Rwanda, where their claims would be processed by Rwandan authorities and, if granted asylum, they would be settled there. The Home Office has confirmed to ICAI that no cost related to the Rwanda agreement is reported as ODA.

- While the number of people who can be relocated under the agreement is in theory uncapped, in practice Rwanda’s capacity to receive asylum seekers relocated from the UK is limited. In the first year, we assume that 500 people are relocated under this scenario.

- Limits to the Home Office’s capacity to detain and remove asylum seekers arriving in the UK irregularly mean that the majority of arrivals (in this scenario, 80%) continue to be allowed to lodge asylum applications in the UK and destitute asylum seekers awaiting a decision continue to be provided with accommodation and support by the Home Office.

4.10 The implications for in-donor refugee costs for this scenario are shown in column 5 of Table 3. The Home Office’s ODA-eligible costs would be somewhat reduced.

Table 3: In-donor refugee costs per activity or scheme, actual spend by the Home Office and DLUHC in 2022 versus illustrated spend for scenarios 1, 2 and 3

| Home Office or DLUHC activity or scheme | 2022 ODA spend | Scenario 1: Full Implementation | Scenario 2: Safe Routes | Scenario 3: Partial Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Office: Initial accommodation through Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC), including hotels and other contingency accommodation | £1,860 million | No longer ODA-eligible | No longer ODA-eligible | £1,488 million (80% of 2022) |

| Home Office: Asylum seeker travel, such as when moving to new accommodation or to attend asylum interviews | £10 million | No longer ODA-eligible | No longer ODA-eligible | £8 million |

| Home Office: Support for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children | £130 million | £130 million | £130 million | £130 million |

| Home Office: Children’s Panel, which advises and assists unaccompanied children through the asylum process | £2 million | £2 million | £2 million | £2 million |

| Home Office: Asylum support – adults and families | £110 million | No longer ODA-eligible | No longer ODA-eligible | £88 million |

| Home Office: Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) | £180 million | £18 million | £18 million | £18 million |

| Home Office: UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) | £8 million | £8 million | £180 million | £8 million |

| Home Office: Modern Slavery Victims Care Contract (MSVCC) | £12 million | £12 million | £12 million | £12 million |

| Home Office: Administration costs for asylum, such as staff costs for processing asylum seekers’ applications for basic support, and for assessing accommodation needs and managing contractors’ provision of accommodation | £17 million | No longer ODA-eligible | No longer ODA-eligible | £13.6 million |

| Home Office: Management and contracted services for asylum seekers, such as the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility contract (AIRE), and fees to AASC or other accommodation providers and cash card providers | £50 million | No longer ODA-eligible | No longer ODA-eligible | £40 million |

| DLUHC: Homes for Ukraine scheme, grants to local authorities and welcome payments for host families | £520 million | £52 million | £52 million | £52 million |

| Total estimated spend on in-donor refugee costs | £2,900 million | £222 million | £394 million | £1,859.6 million |

5. Conclusion

5.1 The three scenarios show a significant drop in ODA spent on in-donor refugee costs if the Illegal Migration Act is implemented in full, and some impact if the Act is partially implemented. To assess the likely scale of the impact on the UK’s aid budget, it would also be necessary to include estimates of gross national income (GNI) for 2024 (since the ODA budget is around 0.5% of GNI). For the financial years 2022-23 and 2023-24, HM Treasury allocated an extra £2.5 billion to the aid budget in light of the sharp rise in spending on in-donor refugee costs, which meant that ODA spending for 2022 was 0.51% of GNI. However, FCDO has not been allocated additional funds for the financial year 2024-25 according to allocation plans published alongside FCDO’s Annual report and accounts 2022-23. For any scenario where the Home Office’s asylum determination backlog remains large and it continues to spend up to £2 billion of ODA on asylum accommodation and support, there would still be considerable pressure on the UK aid programme in developing countries if the 0.5% cap is maintained. FCDO’s forward planning for ODA programme spending in the financial year 2024-25 is currently at £8.3 billion, up from £7.4 billion in 2023- 24, according to allocation plans published alongside FCDO’s Annual report and accounts 2022-23.