ICAI follow-up review of 2020-21 reports

Letter from the chief commissioner

This is the third year that I have led the Follow-up review looking at what has happened with issues we reviewed in the previous year (2020-21). This process of following up our recommendations to maximise the chances of implementing them has always been an important part of ICAI’s efforts to improve UK aid, but in the context of the turbulence we have seen in the last two years, it is more important than ever.

This period, like the one before it, has been affected by the pressures resulting from COVID-19, although their impact was less during the time the government had to implement our recommendations. In addition, the crises in Afghanistan and Ukraine have inevitably diverted many officials from their normal jobs. But it was the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development and successive budget reductions, this year in the context of the reduction of the spending target to 0.5% of gross national income, which have had an even bigger impact across the board. In effect the merger is still under way, with structures and IT systems still being worked through, and priorities not clear until very recently, even though the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office began life as a merged department in September 2020. In the interviews we undertook in this review, officials often mentioned the merger and the delay in setting out the new priorities as a reason why the implementation of our recommendations had been slowed.

The lack of clarity about priorities can best be described as strategic drift. While the Integrated review did provide a high-level framework, to give direction for resource allocation in the aid programme, the first International development strategy since 2015 was awaited. The strategy finally came out in May, as this report was being finalised. It is to be hoped that clarity on the way forward will enable better implementation of ICAI’s recommendations next year.

Meanwhile, we did see some improvements in using our work. There was better cooperation in the process of follow-up, and we saw some strong learning, especially in relation to the area of conflict-related sexual violence, and in relation to maternal health. These benefited from a clearer strategic direction. However, as last year, significantly fewer recommendations were adequately implemented compared to the follow-up to ICAI’s 2018-19 reports.

Moreover, there remain concerns about proper record-keeping and transparency. Given concerns that transparency is seen as less of a priority since the merger, ICAI is carrying out a review examining this important issue for UK taxpayers and other stakeholders, to be published later this year.

Tamsyn Barton

ICAI Chief Commissioner

Executive summary

This report presents the results of our follow-up exercise to assess progress made by aid-spending government departments and funds on addressing recommendations made by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). It covers 11 ICAI reviews in total: we follow up on seven reviews published in the last annual review cycle from July 2020 to July 2021 (the two reviews on the government’s official development assistance (ODA) spending target are followed up together), and we return again to four reviews published in previous cycles to address outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up exercise. Table 1 gives an overview of the follow-up exercises conducted this year.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review title | Publication date |

|---|---|

| Follow-ups | |

| The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group | 31 July 2020 |

| Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition | 16 September 2020 |

| Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers | 30 September 2020 |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme | 14 October 2020 |

| Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, Part 1 and Part 2 | 24 November 2020 & 20 May 2021 |

| Tackling fraud in UK aid | 8 April 2021 |

| UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa | 8 July 2021 |

| Outstanding issues | |

| Assessing DFID’s results in improving maternal health | 30 October 2018 |

| How UK aid learns | 12 September 2019 |

| The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative | 9 January 2020 |

| The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana | 12 February 2020 |

Scoring the government’s progress

Each ICAI review we follow up for the first time is given a score, designating the response to ICAI’s recommendations as adequate or inadequate, illustrated by a tick or a cross. An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow (the response is insufficiently implemented) and we are not convinced by the reasons for the slowness.

We will return to issues where the government response has been inadequate, either as outstanding issues in the next follow-up or through future reviews. Outstanding issues from previous years are not scored, but a decision is made on whether we need to return to them again.

Overview of the response to ICAI’s recommendations

Overall, the government response to ICAI’s recommendations this year has been mixed and progress on recommendations continues to be affected by the institutional, strategic and budget uncertainties following the merger of the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the reduction of the aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI). The response to the follow-up process has nevertheless been stronger than last year, which saw the follow-up exercise hampered by a lack of access to documentation to assess the relevance and effectiveness of government actions. However, access to evidence remains a problem compared with the years before the FCDO merger.

The positive highlights of this year’s follow-up exercise, which show that ICAI’s recommendations have been well used, include the following:

- For the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), we found that the new ‘theory of change’ on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), the PSVI strategy and country plans with key performance indicators are a strong, if delayed, response to ICAI’s concerns about a lack of strategic direction and oversight of the cross-government efforts in this area of UK aid. The theory of change and strategy explicitly address ICAI’s concerns and problem statements.

- We found across the follow-up of three different reviews that the UK government has taken on board ICAI’s recommendation on entrenching a survivor-centred approach to all aspects of its programming related to CRSV and sexual exploitation and abuse, including modern slavery.

- A range of important guidance has been produced for nutrition programming, to guide improved approaches to reaching those most at risk, support the development of healthier diets, integrate nutrition into social protection programming and undertake adequate monitoring and evaluation. The government has also committed to applying an internationally recognised approach to tracking nutrition-related impacts across sectors.

- After lengthy delays, the Ending Preventable Deaths approach paper and the Health Systems Strengthening position paper have been published. Both are of good quality, respond to concerns raised by ICAI in its 2018 review assessing DFID’s results in maternal health, and set a path for the strategic direction for FCDO work on maternal health through to 2030.

- The government has taken a strategic approach to bridging evidence gaps on ‘what works’ in ending modern slavery, through funding the production and dissemination of a range of high-quality research projects. This should support UK and international efforts to combat modern slavery.

There are signs that the merged FCDO has had a positive impact on the response to some of ICAI’s recommendations, while the merger process continues to pose challenges for FCDO’s response in other cases. Looking at the positives first:

- Revisiting the two companion reviews of The UK’s Prevention of Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative and Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers, this year’s follow-up review found a considerably more joined-up approach to addressing the challenges of CRSV.

- African Development Bank Group officials noted in interviews that they welcomed the UK’s stronger engagement and more joined-up approach in their engagement with the Bank, which seems to have been influenced by the merger.

For other reviews, the picture was less positive. For instance:

- Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, Part 1 and Part 2: The government engaged with ICAI’s recommendations, including by exploring ways in which to manage the spending target more flexibly. However, few concrete changes to policy or practice have been proposed that would address the value for money risks identified in the two reviews.

- How UK aid learns: FCDO continued to be absorbed by the process of developing its own systems, policies and strategies, which limited its ability to support efforts to develop a more coherent and joined-up approach to monitoring and evaluation, learning and transparency across the UK aid programme.

- Tackling fraud in UK aid: The demands of the merger, together with continued uncertainty about resourcing while strategic decisions are being made, have contributed to capacity shortages in the FCDO Control and Assurance (counter-fraud) team, which has constrained its ability to respond to ICAI’s recommendations.

- UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Interviewees explained that the slow response to addressing ICAI’s recommendations was partly due to the merger, because there was no new relevant programming in which to implement recommendations.

Cross-cutting issues

The period covered by this follow-up review was characterised by great change and uncertainty in UK aid. The FCDO merger processes, which started in September 2020, are still under way. Large-scale international crises in Afghanistan and Ukraine, as well as the considerable effort involved in responding to the reduction of the UK aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI, have meant less time available to spend on aid programme design and delivery. We discuss two cross-cutting issues that have affected the government’s response to ICAI’s recommendations this year:

- Institutional, budgetary and strategic uncertainties. The restructuring of FCDO is still not complete. Delays in setting the strategic direction for UK aid through the long-awaited International development strategy, published on 16 May 2022, have had knock-on effects on thematic and sector strategies, which cannot be completed if the overall direction and priorities are not set. While waiting for thematic and sector strategies, the planning of new aid portfolios and programmes has often been put on hold. The period since the merger has also seen significant reductions in UK aid spending, resulting from contractions in the UK economy and the decision to reduce the UK’s aid budget temporarily from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI from 2021. This has led to major cutbacks across UK aid and ongoing resource uncertainty as budgets for future programming remained undecided. We found in many of our follow-up exercises that staff and budget constraints have meant that tough choices have had to be made, with negative impacts on the implementation of some of our recommendations. The aid allocations for the 2022-23 financial year could not be finalised until the UK International development strategy had been launched in mid-May 2022.

- Problems of monitoring, record-keeping and transparency. Based on the experience of ICAI reviews, including this one, there has been a reduction in the comprehensiveness of record-keeping and documentation of the UK aid programme since the merger. Although FCDO transparency requirements mean that all programmes should retain and publish key programme documents, such as business cases and results reporting, this has not always been done. If record-keeping is not consistent, FCDO’s ability to assess value for money, learn and build on previous experience is compromised. Retaining institutional memory through good record-keeping is particularly important in periods of great flux, such as the one UK aid is currently undergoing. ICAI found examples in this year’s follow-up exercises of current FCDO teams not having sight of the history of ICAI reviews, leading to a lack of background knowledge, misunderstandings and a sense that there has been less engagement with the reviews’ findings, concerns and recommendations. Linked to this problem of record-keeping, there has been a deterioration in the transparency of UK aid spending since the merger. Aid programme documentation is no longer systematically available for public scrutiny. Whereas ICAI could previously expect to find business cases and annual reports on UK aid programmes available in the public domain, these now often need to be requested from government, and the evidence provided on request varies in its comprehensiveness.

The value of ICAI’s annual follow-up exercises is even greater in a context of institutional flux and strategic drift in FCDO, as these exercises contribute to institutional memory and learning. However, ICAI’s role in supporting institutional memory is limited to the aid areas covered by its review programme. It is therefore crucial that FCDO strengthens its approach to monitoring and record-keeping, to maintain institutional memory for learning. It is also crucial for FCDO to ensure that records are open and accessible, to enable public scrutiny of UK aid spending.

Outstanding issues we will return to again next year

In addition to following up a new set of ICAI reviews next year, we will come back to the following reviews as outstanding issues:

- Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, Part 1 and Part 2: The government engaged with ICAI’s recommendations, including by exploring ways in which to manage the spending target more flexibly. However, few concrete changes to policy or practice have been proposed that would address the value for money risks identified in the two reviews. The government could do more to explore different options in relation to Part 1, Recommendations 2, 3 and 4, which suggest exploring ways of lessening value for money risks and introducing greater flexibility into the management of the 0.7% target; and Part 2, Recommendations 1 and 2, on the use of GNI forecasting and building options for flexing spend into country portfolios and plans. We will therefore be returning to these recommendations.

- Tackling fraud in UK aid: We will return to Recommendations 2, 3 and 4, to assess the extent to which the strains on staff and budgets continue to hinder the government in addressing ICAI’s concerns.

- UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa: We will return to all the recommendations after finding limited actions taken to address ICAI’s concerns. Some important work to develop a methodology for assessing job creation, as well as work on gender inclusion, is taking place, but it is currently too early to tell what impact this work may have.

- The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana: We will return to Recommendation 6 on stronger guidance to ensure the prioritisation of development objectives when ODA is used for initiatives aimed at benefiting both the UK and developing country partners. As the priorities of the new International development strategy start to be implemented, it is crucial that the risks to development objectives and value for money entailed in the government’s integrated approach to aid, trade and investment are addressed as well as the opportunities.

- The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme: Since the planned Modern slavery strategy has not yet been published, we will return next year to assess how it addresses ICAI’s recommendations, including whether it gives sufficient attention to ODA-funded international work to reduce modern slavery in origin, transit and destination countries.

- How UK aid learns: We will return to this review next year, since the recommendations have not received adequate attention as part of the FCDO merger process.

Summarising progress on recommendations per review

Table 2: Overview of progress and scoring for individual reviews

| Our assessment of progress on ICAI recommendations | Score |

|---|---|

| The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group | |

| ICAI’s full review of The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group was published in July 2020, and was scored green-amber. It found that UK aid funding for the African Development Bank Group is good value for money, allowing the UK taxpayer to influence development across Africa. ICAI offered a set of recommendations to help the government evolve its approach to engaging the Bank on issues such as performance management, core resources, environmental and social safeguards, trust fund management and in-country collaboration. There has been notable progress from the UK government in response to most of the recommendations, especially in pursuing a more multilateral approach to promoting improved Bank performance, supporting efforts to expand the Bank’s core resources and deepening strategic collaborations with the Bank on climate finance, crisis response and in the Sahel. The UK has strengthened its engagement on the Bank’s environmental and social safeguards, although it could be engaging on these issues more consistently. Interviewees from the Bank noted that the merged FCDO was followed by renewed engagement and a more joined-up approach. |  |

| Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition | |

| ICAI’s review Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition was published in September 2020, and was scored green-amber. It found that FCDO had exceeded its commitment to reach 50 million pregnant and lactating women and children under five between 2015 and 2020. It also set out recommendations to improve the depth and breadth of the impact of its nutrition work, including through increasing the emphasis on cross-cutting interventions, local systems building and targeting the most marginalised. FCDO has responded clearly and adequately to most of the issues raised in the review. We judge it to have made adequate progress on all of the review’s recommendations. FCDO stakeholders highlighted that the review has been a catalyst for valuable new guidance aimed at strengthening the design and targeting of nutrition interventions, results systems and strategic approaches. FCDO should now prioritise implementing these new approaches to nutrition, ensuring sufficient capacity across the organisation to integrate nutrition-related outcomes and indicators, build local systems and strengthen engagement with people expected to benefit from its programmes. |  |

| Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers | |

| ICAI’s review of Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers was published in September 2020, as a short report accompanying the January 2020 review of The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative. It found that the UK government was a leading actor in international efforts to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) but noted missed opportunities to join up closely related areas of work, in terms of both support to survivors and the sharing of learning on 'what works'. Since the FCDO merger, cross-departmental collaboration between FCDO and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) on tackling SEA by international peacekeepers has improved considerably. The government’s work in this area now has a stronger strategic focus, with the development of a cross-government theory of change on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), which includes SEA by peacekeepers. The strategy sets out a survivor-centred approach, which is also showing in practice, with FCDO contributing funding to the UN Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse. The MOD is in the final stages of creating its own SEA policy, grounded in the CRSV theory of change. There remains an opportunity to strengthen this cross-departmental strategic approach further as the ground has been prepared for the implementation of a survivor-centred SEA approach across all UK aid activities to tackle SEA in peacekeeping missions. |  |

| The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme | |

| ICAI’s review of The UK’s approach to tackling modern slavery through the aid programme was published in October 2020 with an amber-red score. The review found that the UK government played a prominent role in raising the profile of the issue globally but concluded that its work within developing countries was not well positioned to achieve impact, did not build on existing international efforts and experience, and failed to involve survivors adequately. The follow-up found that initial positive steps have been taken. However, staff and budget constraints in 2021, as well as uncertainty about future budget allocations and strategic direction, mean that these have as yet only had a limited impact on programme delivery. The government has prioritised a strong research agenda and taken important initial steps on survivor engagement. There has also been some new evidence of country-level partnerships. However, the responses on mainstreaming, neglected areas, and private sector engagement have been disappointing. The new Modern slavery strategy, which is still under development, will be key to setting the direction and scale of future UK aid initiatives to tackle modern slavery. With the strategy still unpublished, we score the government’s response as inadequate. We will return to this review next year to assess how the strategy addresses ICAI’s recommendations, including whether it gives sufficient attention to ODA-funded international work to reduce modern slavery in origin, transit and destination countries. |  |

| Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, Part 1 and Part 2 | |

| ICAI’s two rapid reviews of Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target were published in November 2020 and May 2021. Both were unscored. The reviews found that the UK government, and in particular DFID/FCDO as spender or saver of last resort, had successfully managed spending to hit the 0.7% target. However, they also noted that a lack of flexibility in the government’s interpretation and pursuit of the target opened up several value for money risks, particularly when there is significant uncertainty about the level of ODA spend required to meet the target. We recognise the effort from the government to engage constructively with ICAI's recommendations. However, we have seen few changes to the way in which the government manages the spending target in response to the main thrust of our recommendations and the value for money risks identified in the ICAI reviews. As a result we will be following up the recommendations again next year. |  |

| Tackling fraud in UK aid | |

| ICAI’s rapid review of Tackling fraud in UK aid was published in April 2021 and assessed the extent to which the UK government takes a robust approach to tackling fraud in its ODA expenditure. It reviewed how five departments prevent, detect, investigate, sanction and report on fraud in their aid delivery chains, and how they manage fraud risk within portfolios, programmes and projects. The follow-up found that the government’s response, led by FCDO, to ICAI’s recommendations has led to important changes, including the establishment of a cross-government ODA Counter Fraud Forum. However, severe resource shortages following the FCO-DFID merger in both the fraud investigations team and the Control and Assurance (counter-fraud) team have hampered the implementation of plans. We therefore judge that the government’s response to Recommendations 2, 3 and 4 is inadequate, despite some initial promising signs. |  |

| UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa | |

| The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is a region of considerable strategic interest to the UK. With one of the youngest populations in the world, a key challenge is youth unemployment, which averages 23% among 15- to 24-year-olds in the Arab states, compared with 14% globally. In response to this context, ICAI examined how effectively UK aid had addressed the challenge of promoting youth employment in the MENA region over the period since 2015. This review was published in July 2021. The government response to the review was limited and tangible actions were largely modest in nature. The limited response seems to have been driven by FCDO’s continued stance that it does not have an explicit youth employment strategy in MENA, as well as ongoing challenges facing the department, especially from the merger, reductions to the aid budget and staff changes. Our 2021 review found that the portfolio of work, including youth employment objectives, was sufficiently large to warrant the review, and the findings remain relevant to the broader macroeconomic work of the department, encompassing employment. We will return to all five recommendations next year. |  |

Table 3: Overview of progress on outstanding issues from earlier reports

| Outstanding issue | Our assessment of progress since last year |

|---|---|

| Assessing DFID’s results in improving maternal health | |

| This is the third time that ICAI has returned to this review, originally published in October 2018, due to the delays in publishing the Ending Preventable Deaths approach paper and Health Systems Strengthening position paper. | Two long-awaited documents, the Ending Preventable Deaths approach paper and the Health Systems Strengthening position paper, were finally published in December 2021. Their publication represents an important milestone and sets the strategic direction for FCDO work on maternal health through to 2030. The latter paper in particular was long overdue, as it had already been in development for several years at the time of ICAI’s maternal health review (2017-18). Both documents are of good quality and respond to ICAI’s concerns, with a strong emphasis on cross-sectoral work, equity, rights and quality of care, and a new commitment to ensuring respectful maternity care. Recent reductions in UK aid have had a dramatic impact on maternal health programming since the ICAI review. Although the uncertainties around future maternal health programming raise concerns about the response to ICAI recommendations, we will not return to this review next year. |

| How UK aid learns | |

| This is the second time that ICAI has returned to this review, originally published in September 2019. The first follow-up concluded that there had been limited progress, largely because the recent departmental merger had created significant uncertainty regarding the new department’s role in cross-government work, thereby disrupting efforts to implement the recommendations. | Only limited action has been taken to date on the recommendations from this review, despite their continued relevance and the amount of time (two and a half years) since the review was published. FCDO has been supporting cross-government efforts to develop the government’s new International development strategy, but has only undertaken limited work to support broader learning on good development practice across departments. FCDO has focused on developing its own evaluation policy, and is not working to develop common monitoring, evaluation and learning standards across government. FCDO’s ongoing work to develop its new aid management and finance systems is also not taking into account the need to complement the systems being used in other aid-spending departments, or the need to generate similar forms of data. This lack of progress can partly be explained by the FCDO merger, which has led to the department focusing on its own institutional development and created uncertainty about organisational structures and processes. However, it is also clear that these recommendations are not receiving adequate attention as a part of the merger process, which could have been used as a vehicle for taking them forward. We will therefore be returning to the recommendations next year. |

| The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative | |

| Last year’s follow-up found that important strategic work was under way and that the commitment to the initiative was strong. However, ICAI was not given sight of the PSVI draft strategy, key performance indicators or the monitoring, evaluation and learning framework, and did not receive programme documents or information on the budget for PSVI-related activities. | There is now improved oversight and direction of cross-government activities related to the Prevention of Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI). FCDO has produced a theory of change for addressing conflict-related sexual violence and a PSVI strategy accompanied by detailed plans for five focus countries with key performance indicators. FCDO has also moved to multiyear funding cycles for PSVI-funded projects. This is a strong improvement. The original ICAI review had criticised the PSVI’s use of one-year funding cycles as inappropriate for programming on sexual violence, since it posed an impediment to the meaningful participation of survivors and heightened the risk of inadvertently doing harm. ICAI finds that the overall action by government is considerable and places the UK’s efforts to tackle conflict-related sexual violence on a stronger, more strategic footing. We will not return to this review next year, but two significant weaknesses nevertheless remain. First, while the PSVI strategy states an ambition to develop a strong monitoring, evaluation and learning framework for the PSVI, this is not yet in place. Second, there is insufficient transparency around PSVI spending, with no programme documents available in the public domain. The issue of transparency in UK aid is the subject of a separate ICAI review, which we expect to publish later this year. |

| The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana | |

| Last year’s follow-up found that responses to four out of the six recommendations were inadequate, partly based on the insufficient relevance of the response and partly due to the lack of evidence made available to ICAI, which made the assessment of progress impossible. | The UK’s approach to aid spending in Ghana remains focused on supporting Ghana’s transition, with reductions in the ODA budget taking place faster than expected. FCDO now acknowledges the need to protect the development gains that it has contributed to, to the best of its ability within a constrained budget environment. The FCDO Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) has been established. ‘Beneficiary engagement’ is now a standard requirement for all country strategy and programme development and the PrOF guide on monitoring and scoring programmes also incorporates consultation with people expected to benefit from the intervention. Delivery framework guidance on programme development now requires full theories of change and articulates outcomes at an appropriate level. However, ICAI’s recommendation on ensuring the centrality of development objectives when ODA is spent, as part of an integrated approach to aid, trade and investment, has not been sufficiently addressed. This recommendation goes beyond the context of Ghana. As the priorities of the new International development strategy start to be implemented, it is crucial that the risks to development objectives and the value for money entailed in the government’s integrated approach to aid, trade and investment are addressed as well as the opportunities. We will return to this issue in next year’s follow-up exercise. |

Introduction

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) provides robust, independent scrutiny of the UK’s official development assistance, to assist the government in improving the effectiveness and impact of its interventions and to assure taxpayers of the value for money of UK aid spending. Our main vehicle for this scrutiny is the publication of reviews on a broad range of topics of strategic importance in the UK’s aid programme. A vital part of these reviews is our annual follow-up process, where we return to the recommendations from the previous year’s reviews to see how well they have been addressed.

This report provides a record for the public and for Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) of how well the UK government has responded to ICAI recommendations. The follow-up process is also an opportunity for additional interaction between ICAI and responsible staff in aid-spending departments, offering feedback and learning opportunities for both parties. The follow-up process is central to our work to support learning and improvements in UK aid delivery and to ensure maximum impact from reviews.

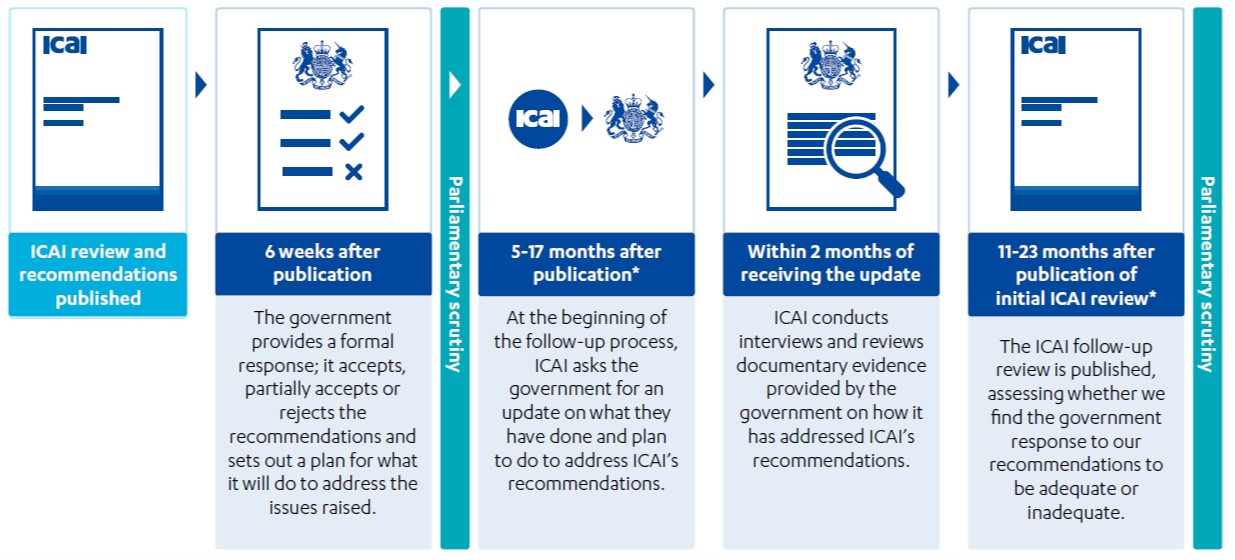

Figure 1: Timeline of ICAI’s annual follow-up process

*We conduct our follow-up assessment on an annual basis, starting in January and publishing in the summer. The follow-up covers a number of reviews which are selected according to their publication date (if a review is only published a few months prior to the follow-up process then it will be covered in the following year). If we are unsatisfied with the government’s progress on any of our recommendations, we then follow up on those areas again during the next year’s assessment.

The follow-up process is structured around the recommendations provided in each ICAI review (see Figure 1 above for an illustration of the process). Soon after the original ICAI review is published, the government provides a formal response (within six weeks). The response sets out whether the government accepts, partially accepts or rejects ICAI’s recommendations and provides a plan for addressing the issues raised. This is typically followed by a hearing, either in the ICAI sub-committee of the IDC or as part of the work of the main committee. The formal follow-up process this year took place between five and 18 months after the publication of the original reviews, the results of which are presented in this follow-up review. The exact time gap between review and follow-up depends on how early in ICAI’s annual review cycle the relevant report was published, but also on other factors such as the timing of other closely related ICAI reviews.

To start the follow-up exercise, in December 2021 ICAI asked aid-spending departments for an update on what they have done and plan to do. This was followed by evidence gathering in January and February 2022, in which we investigated the extent to which the government had done what it promised and determined if this was an adequate response. The findings are reported and scored in this follow-up review. After publication, there will be parliamentary scrutiny of the follow-up review’s findings.

Scoring the follow-up exercises

Each review we follow up for the first time is scored using a tick or a cross, depending on whether we find the overall progress adequate or inadequate. The score takes into consideration the wider context, including external constraints, in which government actions have taken place. It also considers the time the relevant government department or organisation has had to plan and implement changes.

An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow and we are not able to judge their effectiveness (the response is insufficiently implemented).

The third factor – the adequacy of implementation – is not a simple question of checking if plans have been put into practice yet. We take into consideration how ambitious and complicated the plans are, and how realistic their implementation timelines are. Some changes are ‘low-hanging fruit’ and can be achieved quickly, while others demand long-term dedicated attention and considerable resources. An inadequate score due to slow implementation will only be awarded if ICAI finds the reasons provided for lack of implementation insufficient.

This year’s follow-up review covers seven ICAI reviews with a total of 33 recommendations. The two reviews on the UK aid spending target (Part 1 and Part 2) are followed up together. After briefly setting out our methodology, we discuss cross-cutting issues affecting how ICAI’s recommendations have been addressed in the past year. We look at challenges with monitoring, reporting and record-keeping and the risks these pose to institutional memory in the period of upheaval following the merger of the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Linked to this, we also discuss what can be described as strategic drift in UK aid in a turbulent period characterised by great uncertainty in the drawn-out post-merger realignment of priorities, plans, budgets and teams. This section also provides two short case studies of learning journeys seen through the lens of the ICAI review and follow-up cycle, one for the two linked reviews on UK aid’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative and its work to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse in international peacekeeping operations, and a second on strengthening the reporting on and strategic direction of FCDO’s work on maternal health. The section on cross-cutting issues is followed by an account of progress on the seven reviews and four outstanding issues covered by this year’s follow-up review. We sum up with a brief conclusion and a list of the reviews and recommendations we plan to return to again next year.

Methodology

When we follow up on the findings and recommendations of our past reviews, we focus on four aspects of the government response:

- Whether the actions proposed in the government response are likely to address the recommendations.

- Progress on implementing the actions set out in the government response, as well as other actions relevant to the recommendations.

- The quality of the work undertaken and how likely it is to be effective in addressing the concerns raised in the review.

- The reasons why any recommendations were only partially accepted (none of the recommendations were rejected).

We begin by asking the relevant government department or organisation to prepare a brief note, accompanied by documentary evidence, summarising the actions taken in response to our recommendations. We then check that account through interviews with responsible staff, both centrally and in country offices, and by examining relevant documentation, such as new strategic plans, annual reviews, etc. Where necessary or useful, we interview external stakeholders, including other UK government departments, multilateral partners and implementers. To ensure that we maintain sight of broader developments, we also assess whether ICAI’s findings and analysis have been influential beyond the specific issues raised in the recommendations, as well as whether changes in the environment have affected the relevance and/or urgency of individual recommendations.

The follow-up process for each review concludes with a formal meeting between a commissioner and the senior civil service counterpart in the responsible department. At the end of the follow-up process, we identify issues that warrant a further follow-up the following year. The decision takes into account the continuing strategic importance of the issue, the action taken to address it, and whether or not there will be other opportunities for ICAI to pursue the issue through its future review programme.

We also use the follow-up process to inform internal learning for ICAI about the impact of our reviews on UK aid and how we communicate our findings and recommendations to achieve maximum traction with the government.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

The follow-up review addresses the adequacy of the government response to ICAI’s recommendations. Its findings are based on checking and examining the government’s formal response, and its subsequent actions in relation to the recommendations from the review. The time and resources available for this evidence gathering exercise are limited, and not comparable to a full ICAI review.

Cross-cutting issues

Introduction

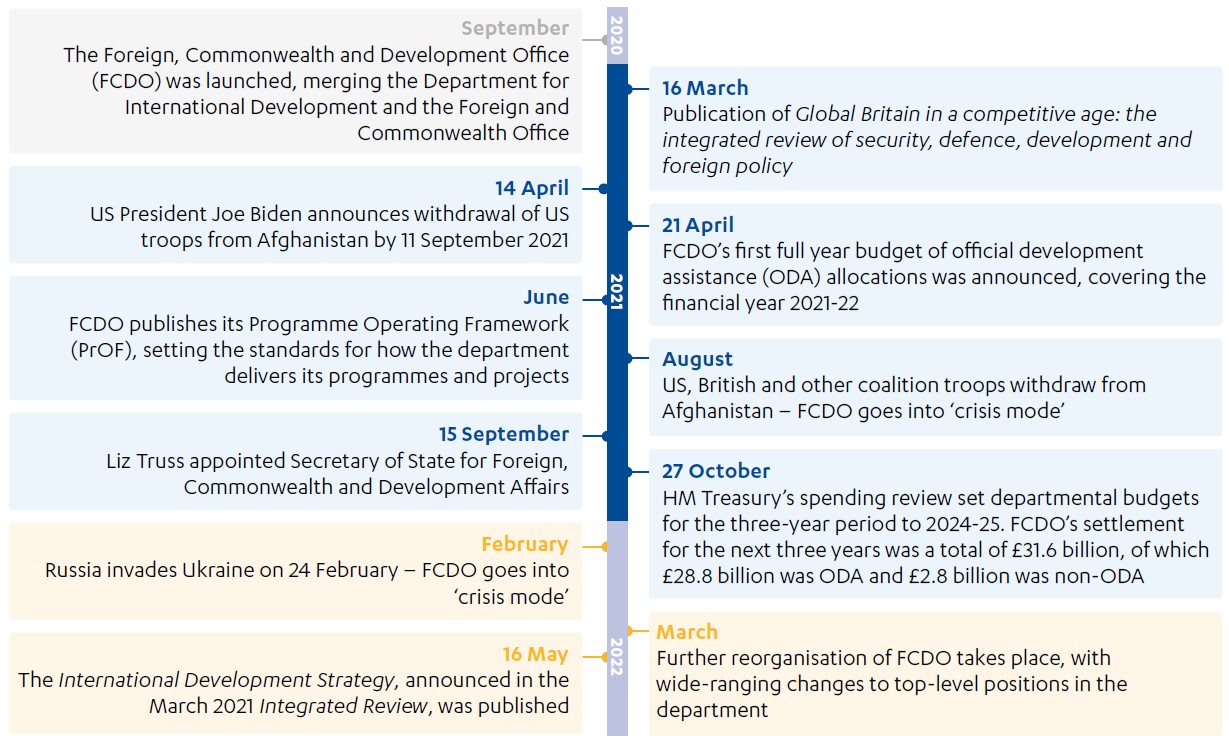

The period covered by this follow-up review continues, like last year, to be characterised by great change and uncertainty in UK aid. The system alignments, structural changes and resource allocations following the merger of the former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020 are still under way. Large-scale international crises in Afghanistan and Ukraine, as well as the considerable work involved in the reduction of the UK aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income (GNI) have meant less time available to spend on aid programme design and delivery. This is evident in the findings from individual follow-up exercises presented in Section 4, which in many cases conclude that government teams have not had the time and resources to address ICAI’s recommendations adequately.

Institutional changes continue to unfold within the new FCDO. While a range of strategic work to set the direction for future aid delivery has been completed in recent months or is in the late stages of completion, such work is often arriving after long delays, as discussed below. The long-awaited International development strategy was launched on 16 May 2022, after being announced in the March 2021 Integrated review. The detailed budgets for the 2022-23 financial year are still being finalised at the time of writing. In this section we discuss two cross-cutting issues that have affected the government’s response to ICAI’s recommendations. We first look at institutional, budgetary and strategic uncertainties that have posed major challenges for the delivery of UK aid. We then turn to problems of monitoring, record-keeping and transparency, which constitute a particular risk for institutional memory and learning in a time of flux.

Figure 2: Timeline of key events affecting the direction and delivery of UK aid after the FCDO merger

Institutional, resourcing and strategic uncertainty in a turbulent year

The significant institutional, resourcing and strategic uncertainty facing the UK aid programme during 2020-21 has posed major challenges for efforts to deliver a strong response to ICAI recommendations during this period.

Although the FCDO merger process began in mid-2020, the process of developing its structures and merging legacy systems continues. This is illustrated by an additional restructuring of the department announced by the foreign secretary in March 2022. The restructuring was primarily in response to the Ukraine crisis, but it contributes to the ongoing restructuring processes since the merger and highlights the fact that the two departments’ legacy project and financial management systems, as well as broader IT systems, are still being run concurrently.

These continuing institutional changes emerged as important contextual factors in the follow-up to several reviews. First, in relation to the How UK aid learns review, which is an outstanding issue from last year’s follow-up exercise, we were told that FCDO has been fully absorbed by the continued process of developing its own systems, policies and strategies. This has limited its ability to support efforts to develop a more coherent and joined-up approach across government to monitoring and evaluation, learning and transparency in other government departments that spend official development assistance (ODA) (24.2% of all ODA spend in 2021). Second, in relation to the review of UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa, we were told that the lack of new projects in the Middle East and North Africa portfolio, through which the recommendations could be pursued, was partly due to the continued demands of completing the process of the merger.

The period since the FCDO merger has also seen significant reductions in UK aid spending, resulting from contractions in the UK economy and the decision to reduce the UK’s aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of GNI from 2021. In 2021, UK aid spending was almost £3 billion lower than in 2020, which has led to major cutbacks across the aid programme and ongoing resource uncertainty. The follow-up to the two Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target reviews identified budget uncertainty as a key factor which prevented FCDO from providing convincing assurance to ICAI that it had allocated future aid spending in a way that limited value for money risks resulting from an inflexible approach to managing the target, and making insufficient use of multilateral instruments to dilute impacts on the ground.

The follow-up to ICAI’s review of Tackling fraud in UK aid found that due to the loss and non-replacement of staff, the FCDO Control and Assurance (counter-fraud) team operated at significantly reduced capacity.

In addition to the recent crises in Afghanistan and Ukraine, a key factor that seems to have added to the institutional and resourcing uncertainty facing the aid programme was the delay in publishing the International development strategy. Following the completion of the delayed Integrated review (first announced in December 2019 and published in March 2021) and the multi-year Comprehensive spending review (October 2021), the new International development strategy (first announced in March 2021) was finally published on 16 May 2022. This year’s second follow-up of the ICAI review of How UK aid learns identified delays to the International development strategy as having constrained more ambitious cross-government coordination on development.

Delays first to the Integrated review and then to the International development strategy have had knock-on effects on other thematic or sector strategies. In the lengthy periods during which such thematic and sector strategies have been under development, uncertainty around priorities and direction has hampered the planning of aid portfolios and programmes. In the case of the reviews followed up by ICAI this year, the theory of change on conflict-related sexual violence, the strategy for the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), the Ending Preventable Deaths approach paper, the Health Systems Strengthening position paper and the forthcoming cross-government Modern slavery strategy have all faced lengthy delays.

This challenging context, and its impact on the reforms required to make UK aid more effective and impactful, highlight the urgency of avoiding further strategic drift. The long timespan for developing strategies, whether for UK aid as a whole or for individual sectors or themes, also poses a value for money concern, as each delay will entail the need for rewrites and updates.

Monitoring, reporting, record-keeping and institutional memory

Based on ICAI’s experience from this year’s and last year’s follow-up exercises, as well as our ongoing review programme, we assess that there has been a reduction in the comprehensiveness of recordkeeping of the UK aid programme since the merger. Although FCDO transparency requirements mean that all programmes should retain and publish key programme documents, such as business cases and results reporting, this has not always been done. For instance, our review of UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa found a case where there was no programme documentation at all, although FCDO was able to provide more documentation on the relevant programme in this year’s follow-up exercise. While ICAI could previously expect to find business cases, with objectives stated, and annual reports on UK aid programmes in the public domain, these now often need to be requested from government. Although this is now improving, the government’s record of providing the necessary documentary evidence on request has been patchy.

Inconsistent record-keeping – and reduced public access to those records – could be seen as a temporary problem during a transition period of merging two departments with different reporting approaches. However, 18 months into this transition period, ICAI is concerned that the expectation of a comprehensive and public account of how UK aid is spent is being eroded. It is notable that the new International development strategy, published in May 2022, does not include an explicit commitment to greater transparency and public scrutiny in the way that the previous 2015 UK aid strategy did. However, in a subsequent response to a written parliamentary question, FCDO stated that it remains committed to the aid transparency standards set out in the 2015 UK aid strategy and it is in discussion with the Cabinet Office to further develop the transparency commitment through revisions to the UK’s Open government national action plan, which will be agreed by August 2022. For instance, in our follow-up of the ICAI review of The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative both last year and this year, we found no programme-related documents in the public domain (a detailed overview of programmes, but without results data, was provided to ICAI on request this year). We returned to our Ghana country portfolio review as an outstanding issue this year due to a lack of documentary evidence provided in last year’s follow-up exercise. This year’s response was more detailed, but ICAI nevertheless did not receive the requested Ghana country programme budget and expenditure information, which would have helped in verifying that actions were being implemented.

To conclude, if records are not comprehensively kept and accessible to internal users and public scrutiny, FCDO’s ability to assess value for money, learn and build on previous experience and practice is compromised. Retaining institutional memory through good record-keeping is particularly important in situations of flux. This is pertinent considering the past two years, with the merger of the FCO and DFID, and the restructuring of departments, teams and individuals within FCDO. ICAI found examples in this year’s follow-up exercises of current FCDO teams not having sight of the history of ICAI reviews, leading to a lack of background knowledge, misunderstandings and a sense in those cases that there has been less engagement with the reviews’ findings, concerns and recommendations.

Box 2: Learning journey: UK aid programming on conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV)

This year, ICAI followed up on the review of Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers and returned again to its review of The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative as an outstanding issue. The two companion reviews were published separately, due to the government at the time treating sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by peacekeepers as separate. ICAI noted that such compartmentalisation was not warranted, since the government’s PSVI and SEA work cover different aspects of the same broader challenge of CRSV.

Both reviews found a lack of strategic direction and cross-government coordination. The PSVI review concluded: “Each department and in-country team is left to interpret the Initiative in line with their own strategic priorities rather than through a unified cross-departmental strategy and concrete objectives”. Both reviews also expressed concern that although the government stated its objective of a survivor-focused approach to its programming, ICAI did not see this objective consistently followed through in the design and implementation of programming.

This year’s follow-up exercise reveals a strong learning journey, led by FCDO, to address ICAI’s concerns. This has placed the government’s programmes to tackle CRSV on a much stronger evidence-based footing and in line with global best practice. Highlights of the learning journey include:

- The creation of a well-evidenced and comprehensive CRSV theory of change which, among other sources, draws on ICAI’s literature review accompanying the PSVI and SEA reviews and steers the government’s approach in the direction ICAI has urged.

- The creation of a cross-government PSVI strategy that builds on the CRSV theory of change and includes comprehensive (but not yet implemented) plans for monitoring, evaluation and learning that directly mentions and addresses ICAI’s recommendation on this.

- The commitment to a survivor-centred approach is more strongly embedded across CRSV-related programming. The survivor-centred approach is central to the PSVI strategy and CRSV theory of change. At the practical level, there has been an increase in focus on using funds to support survivors, such as contributing funding to the UN Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse. FCDO has also now adopted multi-year funding allocations as the norm for its central PSVI projects, which will increase opportunities for sustainable impact and allow more meaningful engagement with survivors.

Box 3: Learning journey: Strategic direction for and results reporting of UK aid on improving maternal health

After returning for a third time to ICAI’s recommendations in its 2018 review Assessing DFID’s results in improving maternal health, we are pleased to see the results of a clear, if somewhat slow, learning journey within FCDO on the importance of long-term planning and strategic direction in this area, and of improved results reporting. The review was originally scored amber-red. The initial reactions from DFID were not all positive, as in the case of the fourth recommendation on more rigorous results reporting, which the government said it was already partly implementing. However, ICAI’s first follow-up in 2019 did see many positive developments in relation to ensuring greater impact, equity and sustainability in maternal health programmes. ICAI decided to keep open the option of returning to the review the following year if two central but not yet finalised strategic documents were not published. This turned out to be a good decision. In a time of great change for UK aid, ICAI’s attention over subsequent years helped to maintain the focus on the importance of finalising and publishing the Ending Preventable Deaths (EPD) approach paper and Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) position paper, both of which were launched in December 2021.

The EPD approach paper provides a more realistic approach to reporting, shifting away from short-term outputs to UK aid’s contribution to long-term impact in countries.

The HSS position paper helps to ensure that work on maternal health is integrated into a cross-sectoral approach focused on equity, rights and the quality of care.

However, the significant reductions in programming on maternal health since the 2019-20 financial year and the uncertainty around future funding make it more important than ever that funding priorities are set on a sound basis. Without the EPD approach paper and the HSS position paper in place, this would be an even more challenging task.

Conclusion on cross-cutting issues

The value of ICAI’s annual follow-up exercises is even clearer in a context of institutional flux and strategic drift in FCDO, as these exercises contribute to institutional memory and learning. However, ICAI’s role in supporting this is limited to the aid areas covered by its review programme. It is therefore crucial that FCDO strengthens its approach to monitoring and record-keeping and ensures that such records are open and accessible, both to maintain institutional memory for learning and to enable public scrutiny of UK aid spending. Some of the issues raised in this discussion will be addressed through ICAI’s forthcoming review of transparency in UK aid.

Findings from individual follow-ups

This section presents the results of our follow-up assessments of the government’s responses to ICAI’s recommendations. Each review we have followed up on is presented individually, with a focus on the most significant results and gaps in the government response.

We begin by presenting the findings for the eight reviews we are following up on for the first time since their publication. The follow-up exercises are presented chronologically, starting with the review with the earliest publication date, The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group. For each review, we assess government progress recommendation by recommendation, before summing up and scoring the overall response to ICAI’s recommendations as adequate or inadequate.

We then turn to the four outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up process. None of the outstanding issues are scored, but a decision is set out on whether we will return to them again next year.

The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group

There has been notable progress from the UK government in response to most of the recommendations, especially pursuing a more multilateral approach to promoting improved Bank performance, supporting efforts to expand the Bank’s core resources and deepening strategic collaborations with the Bank on climate finance, crisis response and in the Sahel. The UK has strengthened its engagement on the Bank’s environmental and social safeguards, but it could be engaging on these issues more consistently. Interviewees from the Bank noted that the merged FCDO was followed by renewed engagement and a more joined-up approach.

ICAI’s full review of The UK’s support to the African Development Bank Group was published in July 2020, and was scored green-amber. This follow-up review covers a period of almost a year and a half since the government published its response. In addition to a document review, this follow-up incorporated insights gathered from interviews with Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) staff centrally and in Uganda, as well as engagement with a select group of senior Bank officials.

The main recent contextual change that has helped shape the government’s response is the formation of FCDO. This is reported to have stimulated greater engagement with the Bank, in a more joined-up way, which has been welcomed by senior Bank officials. There has been more ministerial involvement in the Bank since the FCDO merger, beginning with the minister for Africa at the time, James Duddridge, attending the Bank’s annual meetings. There has also been greater engagement to support the Bank’s level of financing (including through the UK’s ‘Room to Run’ guarantee, which will unlock up to $2 billion of Bank finance, with half for climate adaptation), crisis response and in relation to the Sahel. Bank staff who were interviewed had valued this renewed engagement.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| FCDO should minimise unilateral reform interventions – such as the 2017 Performance Improvement Plan – that could undermine the multilateral nature of the Bank’s governance structure as well as the UK’s reputation as an honest broker. | Partially accepted |

| FCDO should take a broader view of value for money than cost-to-income ratios, and focus on ensuring that key areas of understaffing, such as fragile and conflict-affected states and safeguards, are addressed. | Accepted |

| FCDO should pay particular attention to ensuring that the Bank’s environmental and social safeguards are implemented on the ground. | Accepted |

| If FCDO is to channel more resources to the Bank via Bank-managed trust funds, it should help to build the Bank’s capacity to manage such funds, including technical assistance to strengthen fiduciary and results management. | Accepted |

| Government country teams could do more to identify synergies with Bank investments, thus encouraging closer working, better information flows and better-informed oversight. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: FCDO should minimise unilateral reform interventions – such as the 2017 Performance Improvement Plan – that could undermine the multilateral nature of the Bank’s governance structure as well as the UK’s reputation as an honest broker

Following a second consecutive unsatisfactory Department for International Development (DFID) annual review, in December 2017 DFID decided to place the Bank under a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) – the standard tool used by the department to improve programme performance. ICAI’s original review confirmed the Bank’s view that the PIP was a unilateral intervention by the UK which ran counter to the multilateral nature of the Bank. It highlighted the risks that if other countries started to promote their own reform conditionality, this would raise the transaction costs of Bank reform to unsustainably high levels. The review also considered that the PIP could damage the relationship between senior management at the Bank and the UK. It therefore recommended that the UK minimise unilateral reform interventions.

In its response to this recommendation, FCDO accepted that the bilateral nature and timing of the PIP posed challenges for its relationship with Bank management. It also noted that through the ADF-15 negotiations, concluded in December 2019, it had pursued an alternative approach to incentivising stronger performance, which involved agreeing a performance tranche of £102 million for the final year of the funding round, to be disbursed if ADF-15 reform commitments were implemented. The UK was the only donor to apply a performance tranche to ADF-15.

In interviews carried out for this follow-up, FCDO noted that it did not currently have plans to apply a performance tranche to its forthcoming pledge to ADF-16, partly due to its view that the Bank’s performance has improved. It was clear that its approach to engaging the Bank on performance is now couched in more multilateral terms. However, the UK has not formally ruled out linking part of its future contributions to performance in the Bank.

Recommendation 2: FCDO should take a broader view of value for money than cost-to-income ratios, and focus on ensuring that key areas of understaffing, such as fragile and conflict-affected states and safeguards, are addressed

The original review found that, although the Bank is relatively small compared with other multilateral development banks and cannot achieve the same economies of scale in core functions, its cost-to-income ratio is lower than that of its peers. The review concluded that this context risks damaging the Bank’s effectiveness, and that there was a particular need to invest in the Bank’s core functions for preparing, appraising, supervising and delivering programmes effectively. It also noted that UK priorities such as increasing capacity in fragile states and leveraging private finance would be hard to promote while continuing to push the Bank’s core costs down. It therefore recommended that the UK should promote a broader perspective on value for money at the Bank, which recognised that this would require adequate core capacity to support operations.

In interviews for this follow-up, FCDO noted that following its acceptance of this recommendation, it had been focused on trying to ensure that the Bank has sufficient personnel in core functions. It also noted that it had clearly stated that if the Bank can make the value for money case for extra resources it could and should do so. The Bank also acknowledged that the UK had approved additional positions for key functions each year, which had helped to facilitate the recruitment of ten new positions in fragile states and 21 new environmental and social (E&S) safeguards positions.

While progress in expanding staffing in fragile states and on safeguards has been modest, it should be noted that the UK has limited influence over the resourcing decisions made by the Bank’s Board, and that the UK’s representation at board level is shared with Italy and the Netherlands.

Recommendation 3: FCDO should pay particular attention to ensuring that the Bank’s environmental and social safeguards are implemented on the ground

The original review found that, although the Bank’s E&S safeguard policies are broadly fit for purpose, there was a severe shortage of specialist staff at headquarters and in country offices available to implement these policies. Moreover, it found that a culture of ensuring respect for E&S safeguards was not sufficiently embedded in the organisation, creating the risk that pressures would emerge to cut corners.

In accepting the review’s recommendation to support development of the Bank’s E&S standards implementation better, the government noted that the FCDO Minister for Africa had re-emphasised the importance of institutional reforms, including improved safeguarding capacity, at the African Development Bank Group (AfDB) annual meeting in August 2020. It also noted that it would be monitoring the outcomes of a skills audit that was ongoing at the time, to ensure that timely progress was made on aligning the Bank’s skills and competency needs, including in relation to E&S safeguards. While not assuming a leading role among development partners on this issue, the UK government has taken important steps to support and monitor the Bank’s progress in E&S safeguards.

In the period since its response, Bank staff noted that, while the UK had not been a leading voice in strengthening E&S standards, it had worked alongside others to ensure that safeguards standards are high and, at the same time, were implemented proportionately and on a risk-adjusted basis. UK efforts to secure greater core resourcing for the Bank and reduce staff vacancy levels (as discussed under Recommendation 2 above) have also been helpful for ensuring that there is adequate capacity to uphold strong E&S standards. The UK is engaging closely on the process of developing the AfDB’s new E&S safeguards policy, which is scheduled for approval later in the year.

Recommendation 4: If FCDO is to channel more resources to the Bank via Bank-managed trust funds, it should help to build the Bank’s capacity to manage such funds, including technical assistance to strengthen fiduciary and results management

The original review noted that the lack of trust fund activity might reflect a lack of confidence on the part of partners in the Bank’s management capabilities. This in turn could create a vicious circle where the Bank was unable to strengthen its skills through lack of trust fund management opportunities. It was therefore recommended that, if the UK were to contribute to Bank trust funds, it should help build its capacity to manage them.

The government’s response to the original review noted that the AfDB was being considered as a possible delivery partner for several programmes that were being developed, and that it would review the need for additional technical assistance to support management of these programmes as part of each proposal.

FCDO’s principal contribution to addressing this recommendation over the last 18 months has been to support the design of the Bank’s new trust fund policy, approved by the Bank’s board in 2021, which the UK executive director was reportedly active in shaping. However, this policy does not address reforms to fiduciary, safeguards and monitoring and evaluation systems – the principal concern of the review’s finding on trust funds.

Recommendation 5: Government country teams could do more to identify synergies with Bank investments, thus encouraging closer working, better information flows and better-informed oversight

The original review found that information flows between the Bank and the UK were minimal at country level, which was impeding effective decision-making by the UK and opportunities for collaboration with the Bank in regions such as the Sahel and in key sectors (for example to combine UK investments in rural market access with the Bank’s investments in community road building). The review did, however, note that UK country teams had tight administrative budgets, which posed challenges for monitoring the AfDB on behalf of headquarters. It therefore recommended that FCDO country teams did more to develop synergies with the Bank. FCDO accepted this recommendation.

Through this follow-up review, FCDO staff noted that a mailing list for staff working in all FCDO country offices had been initiated for sharing information about the Bank’s policies, projects and other activities. This type of information-sharing reportedly helped stimulate engagement between FCDO staff in Sierra Leone and in headquarters to use central-level interventions with the Bank to address local delivery problems.

FCDO officials interviewed in Uganda confirmed that they had attended a recent training session organised by FCDO’s International Financial Institutions Department on the work of the multilateral and regional development banks. Insights shared in these interviews also suggested that overall there had been the right level of engagement between FCDO and the Bank in Uganda, although COVID-19 had constrained this engagement.

Conclusion

FCDO’s response to this review has been adequate. The FCDO merger has been accompanied by a more joined-up approach and stronger senior engagement with the Bank. This renewed engagement is valued by the Bank’s staff. The most important recommendation, Recommendation 1 on multilateral working, has clearly been taken on board by the government, and there is satisfaction about this in the Bank. FCDO has been active in developing deeper collaborations with the Bank centrally and in strategically important countries and regions on a range of issues (Recommendation 5). FCDO’s contribution to the issues around value for money (Recommendation 2) and implementation of safeguards on the ground (Recommendation 3) have been less tangible; improvements have taken place but the UK has not taken a leading role among development partners on this issue.

Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition

FCDO has responded clearly and adequately to the majority of issues raised in the review. We judge it to have made adequate progress on all of the review’s recommendations. FCDO stakeholders highlighted that the review had been a catalyst for valuable new guidance aimed at strengthening the design and targeting of nutrition interventions, results systems and strategic approaches. FCDO should now prioritise implementing these new approaches to nutrition, ensuring sufficient capacity across the organisation to integrate nutrition-related outcomes and indicators, build local systems and strengthen engagement with people expected to benefit from programmes.

FCDO has responded clearly and adequately to the majority of issues raised in the review. We judge it to have made adequate progress on all of the review’s recommendations. FCDO stakeholders highlighted that the review had been a catalyst for valuable new guidance aimed at strengthening the design and targeting of nutrition interventions, results systems and strategic approaches. FCDO should now prioritise implementing these new approaches to nutrition, ensuring sufficient capacity across the organisation to integrate nutrition-related outcomes and indicators, build local systems and strengthen engagement with people expected to benefit from programmes.

ICAI’s results review Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition was published in September 2020, and was scored green-amber. This review reported that FCDO had exceeded its commitment to reach 50 million pregnant and lactating women and children under 5 between 2015 and 2020. It also set out six recommendations for improving the depth and breadth of the impact of its nutrition work, including through increasing the emphasis on cross-cutting interventions, local systems building and targeting the most marginalised. These were all accepted by the government.

This follow-up review examines the progress made in addressing these recommendations, and the challenges still to be met in fully implementing them. The analysis is informed by an extensive document review and interviews with 11 FCDO officials. It also takes into account the extensive changes in context since the government responded to the review, including how the emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic and reductions to the UK aid budget have diminished the level of resources available to strengthen the nutrition portfolio and caused disruption to the mechanisms used to report against progress.

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| FCDO should capture and communicate progress against all goals in its nutrition strategy, including strengthening systems and leadership for improved nutrition. | Accepted |

| FCDO should strengthen statistical capacity and quality assurance in-country and centrally, to support more accurate measurement of programme coverage and convergence, and to use the data to improve nutrition programming. | Accepted |

| FCDO should strengthen systems for identifying and reaching the most marginalised women and children within its target groups. | Accepted |

| FCDO should gather citizen feedback more consistently to help improve and tailor its nutrition programmes. | Accepted |

| FCDO should scale up its work on making sustainable and nutritious diets accessible to all, to help address the double burden of malnutrition, through nutrition-sensitive agriculture and private sector development. | Accepted |

| FCDO should work more closely with its partners to achieve the convergence of nutrition interventions, by aligning different sector programmes to focus on those communities most vulnerable to malnutrition. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: FCDO should capture and communicate progress against all goals in its nutrition strategy, including strengthening systems and leadership for improved nutrition

The original review noted that because the tracking and communication of results from DFID’s nutrition work placed a strong emphasis on the goal of reaching 50 million women and children between 2015 and 2020 through nutrition interventions, it failed to address results on other goals vital to global progress on nutrition. Neglected areas of reporting were identified as building national systems for promoting nutrition, progress in nutrition-sensitive programming in other sectors, pursuing global leadership on nutrition and effectively leveraging the private sector’s role.

The government’s response to this recommendation noted the importance of its developing approaches to tracking and reporting on a wider set of results, and stated that work to achieve this was ongoing. Through this follow-up we reviewed four interlinked guidance documents on nutrition programming produced by FCDO through the Technical Assistance to Strengthen Capacities (TASC) project, as part of the Technical Assistance for Nutrition (TAN) programme, one of which aimed to promote a multi-sectoral approach to addressing malnutrition. This multi-sectoral approach is also being promoted by the emphasis on nutrition in FCDO’s new approach for ending the preventable deaths of mothers, newborn babies and children, as well as through a commitment to apply the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) nutrition policy marker for tracking nutrition interventions across all of FCDO’s official development assistance (ODA) programmes. However, due to work on updating IT systems in FCDO following the merger, and linked technical challenges, it was expected that the UK will only be fully reporting against this marker in 2024. It will also be important for FCDO to share the now-published TASC guidance10 externally and to undertake external engagement on it.

FCDO has also made progress in ensuring that there is improved and more systematic monitoring of the impact of its flagship centrally managed TAN programme in supporting UK global leadership on nutrition, promoting global financing of nutrition and expanding the coverage of nutrition services.

Recommendation 2: FCDO should strengthen statistical capacity and quality assurance in-country and centrally, to support more accurate measurement of programme coverage and convergence, and to use the data to improve nutrition programming

The original review found that capacity to adhere to DFID’s methodology for tracking quantitative results in terms of the reach of nutrition programmes was not coherent across country offices, which had led to inconsistencies in results reporting across countries. It also found that results data was not systematically used to guide programme design, to drive a greater focus on the most marginalised or to inform advocacy and systems building work. The review therefore recommended that DFID strengthen its statistical capacity and quality assurance of results reporting.

In response to this recommendation, the government stated that it would reassess the current methodology for monitoring the reach of its nutrition-related programmes, develop a tool to help country teams apply a multi-sector results methodology, develop guidance for effective monitoring of programmes and undertake a review of nutrition data to identify where FCDO could add most value to strengthen government data systems for nutrition targeting and tracking.