New blog – The use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity

10 Feb 2020

ICAI Chief Commissioner Tamsyn Barton writes about our recent mutual prosperity event

Recent media reports about the future of UK aid have increasingly focused on whether the aid programme could be used to provide more immediate benefits to the UK, as well as developing countries. In light of this, it was timely that at the end of January, we hosted a panel discussion based on our recent information note, The use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity.

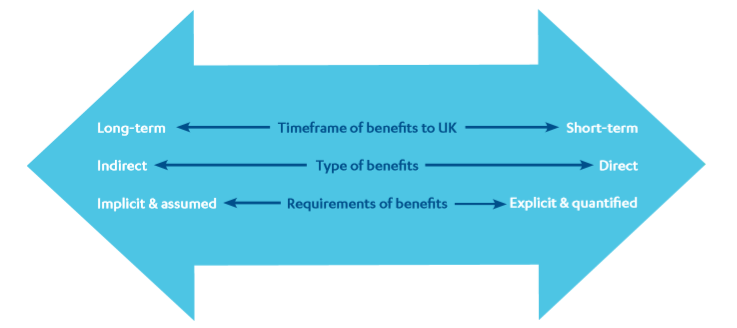

Published in October, the note provides a snapshot of the UK’s current approach to the mutual prosperity agenda. You can read it in full here but, in short, we found that although there is no single UK strategy or definition for mutual prosperity activities, the concept is becoming increasingly prominent in government documents. And although departments are currently taking a cautious approach, it seems likely they will come under more pressure to use aid in this way – creating a need for a clearer set of rules.

Our event, expertly chaired by Simon Maxwell, former director of the Overseas Development Institute, was therefore a chance for experts from across the aid community and beyond to discuss the issues we raised in more detail. What are the risks of a mutual prosperity approach – and what are the opportunities? Can aid really deliver the best of both worlds: poverty reduction in the recipient country, which of course should be the primary focus of aid programmes, while benefiting the UK at the same time? It took place immediately following the UK Africa Investment Summit, which is seen by the Government as a flagship event in this context.

Our first speaker, Sir Tim Lankester, gave a personal account, making clear that mutual prosperity is not a new concept, with aid historically having been tied to British suppliers. As Permanent Secretary at the Overseas Development Administration from 1989 to 1994, he had seen at first hand the disadvantages of tied aid, especially under the Aid and Trade Provision (ATP) where lack of competition and “policy capture” by UK private interests had led to much wasteful spending. He described how this had reached its nadir with the Pergau Dam in Malaysia – with aid being provided against the advice of officials for an uneconomic project which was also linked to a secret arms deal. In the wake of the political fall-out from Pergau, the ATP scheme was abolished and UK aid was in due course untied. Sir Tim said that although in principle there might be scope for aligning UK aid more closely with our commercial interests, it needed to be recognized that the commercial interest could too easily be at the expense of, rather than complementary to, the development and poverty reduction objective, as had been the case in earlier years when aid was tied. He added that the stronger legislative framework governing aid since 2002 plus oversight by the ICAI made it less likely that there would be a repetition of past mistakes. Nonetheless, he concluded it would be right for aid spending departments to adopt a cautious approach.

A different perspective was given by our second panel member. Dr Emma Mawdsley, Director of the Margaret Anstee Centre for Global Studies and Geographer at Cambridge University, told us that, in her view, there was “nothing inherently wrong” with the idea of mutual prosperity, but that the approach should recognise that win-win is not always possible, and focus less on economic development and more on social issues such as the global environmental crisis, workers’ rights and social welfare. One solution, she suggested, could be to separate out the aid budget, ringfencing 0.5% for poverty reduction and (in)equality goals, with a further 0.5% designed to meet the growing challenges of partnerships with middle-income countries, mutual prosperity goals, global public goods, and some forms of economic diplomacy. The Center for Global Development’s Ian Mitchell later questioned this from the floor, asking how such ringfencing of the first 0.5% would be enforced.

Save the Children’s Director of Global Policy, Advocacy & Research, Simon Wright, brought an INGO perspective to the panel. He explained that NGOs want aid to be transformative and to reduce inequalities, and if donors are focusing on getting economic benefits for themselves, there is a risk projects may not focus on the poorest countries and people. You can read his interesting blog about the event here.

Our final member of the panel, Arup’s James Kenny, gave a private sector view, stressing the need for aid to focus on developing institutions, skills and governance in order for it to be most effective and best value. He talked of how the private sector can bring discipline, for example in ensuring proper scoping and “no white elephants”. But he also noted that it was not, in his view, the private sector demanding more direct benefits from aid. He felt that most companies would be worried about the reputational risks of being seen to benefit.

I was pleased to see a diverse and engaged audience in the room, with representatives from across Whitehall, academia and the aid sector. Members of the audience spoke about the importance of the Prosperity Fund – the first UK aid instrument to be explicit about the pursuit of secondary benefits while remaining compliant with the poverty reduction requirements of the International Development Act, and the question of what trade-offs were involved. We also heard interesting points about the role of the Sustainable Development Goals in catalysing investment ‘beyond aid’, including tackling climate change; how the increasing focus on mutual prosperity was often due to requests from partner countries; and the challenges of assessing whether aid is designed to achieve poverty reduction. It was argued by one participant that there was a long history stretching back to colonial times, with the risks of replicating the exploitation. The role of Development Financing Institutions was also highlighted.

We at ICAI are careful to take a balanced view on this issue – there are both benefits and risks to a mutual prosperity approach, and the future direction of policy is a matter for government – but, like others, we are concerned about the risks to aid effectiveness. I’d like to thank everyone who joined us: we will of course continue to keep a close eye on how the mutual prosperity agenda develops. In our view, one major difference from the days of the Pergau scandal is that ICAI is there to provide independent scrutiny.

Meanwhile do look out for more ICAI events in future.